Cameron Blevins (March 31, 2021)

Introduction

US Post Offices was created by Cameron Blevins and Richard Helbock. It is a spatial-historical dataset containing records for 166,140 post offices that operated in the United States between 1639 and 2000. The following is a data biography detailing how the dataset was created and and how it should be used.

Who made the data and why was it created?

Richard W. Helbock (1938-2011) collected the historical data for US Post Offices. Cameron Blevins discovered his work after Helbock had already passed away, Helbock’s research was directly responsible for the resulting dataset. In order to give him proper attribution, Blevins has included him posthumously as a co-creator. A geography professor, Helbock was also postal historian and leader in the philatelic community, including founding the journal La Posta: A Journal of American Postal History in 1969. Helbock spent decades researching the history of the US postal system. This culminated between 1998-2007, during which he published the eight-volume series United States Post Offices, which in his words was “the first attempt to publish a complete listing of all the United States post offices which have ever operated in the nation.” Each volume covered a different region of the United States, and listed information about thousands of individual post offices from that region including their name, county, state, and years of operation.

In addition to the eight printed volumes of United States Post Offices, Helbock produced a Microsoft Access Database of his research to accompany them that was sold on a CD-ROM. This was one of the key decisions that would eventually allow for his work to become US Post Offices. The second decision that made this possible came from his wife, Catherine Clark. After Helbock passed away in 2011, Clark took over many aspects of her late husband’s work - including continuing to make Helbock’s dataset available for purchase online. US Post Offices would never have been created without her contributions.

The primary motivation behind Helbock’s creation of United States Post Offices was for the purposes of philately, or stamp collecting. His volumes were designed as reference books to meet the needs of stamp collectors who could use them to help determine the scarcity (and therefore approximate value) of a postmark from any particular post office. However, Helbock was also keenly interested in the history of the postal system more broadly, which also informed his research.

Cameron Blevins completed the data processing necessary to turn Helbock’s research into a historical-spatial dataset. In 2013, Blevins was a PhD student at Stanford University doing research for his dissertation. After spending months transcribing post office records by hand, he discovered Helbock’s dataset online and purchased the CD-ROM from Catherine Clark. He began working on a geocoding process to try and turn Helbock’s historical data into spatial data, an early version of which he used to complete his dissertation. He continued to refine the geocoding process, eventually arriving at the steps described in more detail in the US Post Offices Github repository.

The primary motivation for Blevins to create US Post Offices was for academic research. In particular, he developed the dataset in order to analyze the history of the western postal system in the late 1800s. He released the dataset in 2021 to coincide with the publication of his book, Paper Trails: The US Post and the Making of the American West.

What’s in the data?

US Post Offices contains 166,140 records of post offices that operated in the United States. Each individual record represents information about a single post office, including its name, location, and approximate dates of operation. It includes post offices that operated within the modern boundaries of fifty US states. The earliest post office in the dataset opened in 1639 and the most recent in 2000.

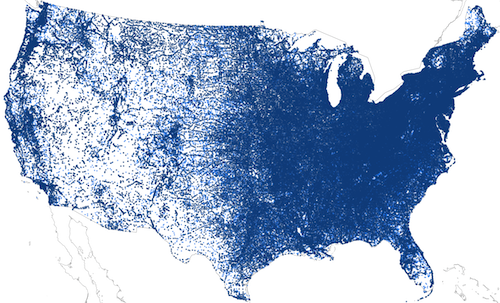

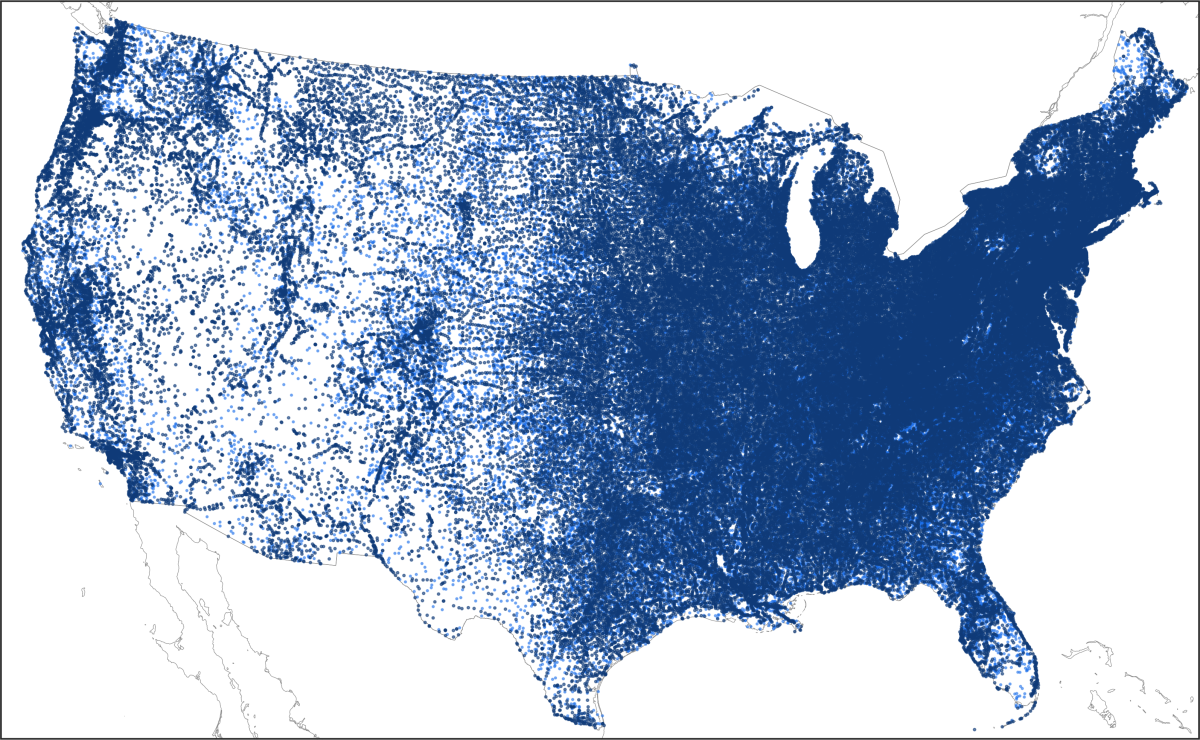

Records from `US Post Offices` in the contiguous United States. Darker points represent exact locations and lighter points are randomly located within their surrounding county.

Records from `US Post Offices` in the contiguous United States. Darker points represent exact locations and lighter points are randomly located within their surrounding county.

US Post Offices includes two main data files. The first file, us-post-offices.csv, contains geographical coordinates only for those post offices that were successfully geocoded using the process described below. The second file, us-post-offices-random-coords.csv, is an alternative dataset that contains geographical coordinates that were semi-randomly assigned to post offices that were not successfully geocoded. You can find documentation for these the specific fields used in the two files in us-post-offices-data-dictionary.csv.

How was the data created?

The creation of US Post Offices can be broken into two stages: archival research compiled by Richard Helbock and data processing by Cameron Blevins.

Stage 1: Archival Research

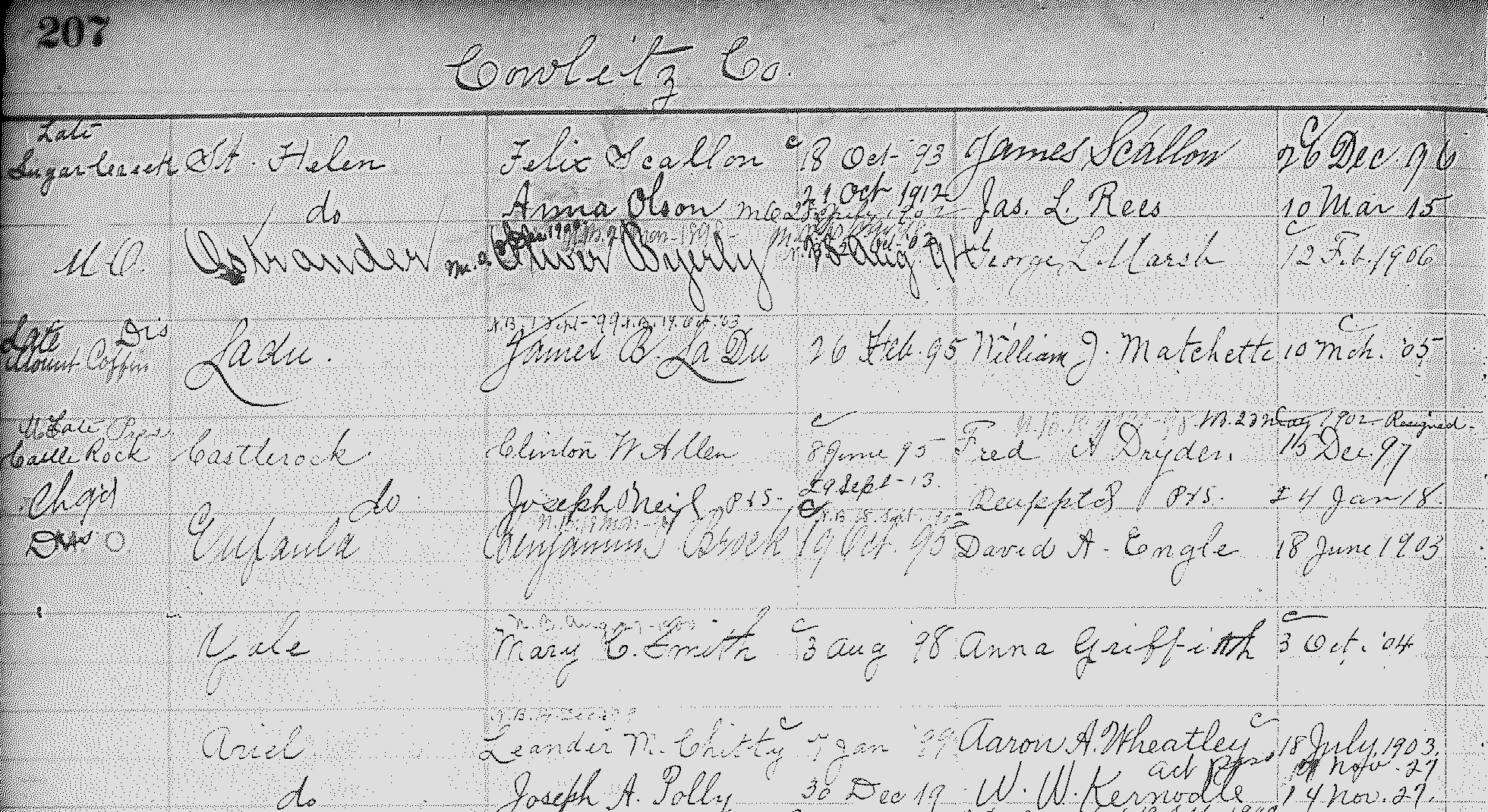

Richard Helbock created a dataset of post offices over several decades of archival research from the 1970s to the early 2000s. The main source for this information was the US Post Office Department’s Records of Appointments of Postmasters, in which the Department recorded information about postmaster appointments at the nation’s post offices.

Microfilmed page from Records of Appointments of Postmasters (Roll 136, Cowlitz County, Washington State)

Microfilmed page from Records of Appointments of Postmasters (Roll 136, Cowlitz County, Washington State)

Helbock also consulted many other kinds of sources, including lists and collections of post offices created by other philatelists and postal historians. The major challenge he faced in compiling his dataset was to decide what, exactly, constituted a single record for an individual “independent post office.” As he noted, what should he do if a post office changed names from “Hillsborough” to “Hillsboro”? Should he leave this as a single post office with the new name, or create two separate records? What if that post office changed locations, or closed for a few years and then re-opened? Helbock helpfully provided documentation about the decisions he made when collecting and recording information in the introductions to his eight volumes. Many of these decisions revolved around the nature of historical post offices prior to the early 20th century, when they were much more fluid entities than they are today.

- General approach:

- Helbock: “The overall rule of thumb applied to the listing of post office names was “Keep it Simple.” In other words, if the choice came down to making a double listing or a single listing for a particular post office with a minor name change due to spelling differences, the single listing was chosen. There are, however, many exceptions to this rule.”

- Closings and Re-Openings:

- Caveat: 21,040 post offices (12.7% of the total) were were NOT in continuous operation between their established and discontinued years. For any given year, there is a small chance that they were actually temporarily closed.

- Unlike today’s post offices, it was common for pre-20th century post offices to temporarily shut down their operations before re-opening months or even years later. This process could happen multiple times for the same post office. Rather than making a new post office record, Helbock decided to use a 10-year cutoff: if the post office was closed for less than 10 years before re-opening, he kept it under the same record. If it remained closed for 10 years or more before re-opening, he treated it as two separate post offices and created a second record for the “new” post office.

- Helbock did not record detailed information about all of these closings and re-openings. Instead, he summarized this in a column in his dataset that was a simple binary of whether or not the post office was in continuous operation between its established and discontinued date.

- Location changes:

- Caveat: Historical post offices switched locations with some frequency. For example, if a new postmaster was appointed they might move the post office from the town’s hotel to their own general store a mile up the road. These kinds of changes are NOT captured in the dataset.

- Helbock: “In the case of post offices which changed locations with the appointment of new postmasters, it was decided that a single listing would be sufficient so long as the office remained in continuous operation, or experienced a break in service of less than 10 years.”

- Name changes:

- Caveat: Historical post offices could change names, which are difficult to capture. For the purposes of the dataset, this means that not every “established” year for a post office represents the opening of a brand-new office, and not every “discontinued” year represents a post office closure.

- Helbock: “A major change of name is treated as a discontinuance, as is conversion of an independent office to the status of station or branch.”

- For instance, if a post office changed from “Albany” to “Zeb’s Store,” he made a second record in his dataset, even if it may have been the same physical post office. This means that for a small percentage of post office records, the year they were “discontinued” in the dataset may have represented a change of name rather than a closure. Similarly, an “established” year may have represented a new name for an ongoing operation, rather than a brand-new post office.

- Helbock: “Post offices which experienced a name change from a two word to a one word format are typically listed only under the form which was in use for the longest period of time.” For instance, Helbock did not create a second record if a post office changed from Browns Ville to Brownsville.

- States and Counties:

- Helbock only collected information about post offices that operated in areas that eventually became US states. This does not include territories such as Puerto Rico.

- Helbock: “Counties given for post offices in this list are those in which the office, or its site, are currently located. No attempt has been made to list county assignments for early day offices which do not coincide with current county boundaries.”

- Essentially, Helbock assigned post offices counties at the time in which he was collecting the data (ie. the late 1900s) rather than the county at the time in which the post office was operating. These are often the same county, but the boundaries of a surrounding county may have shifted so that its modern location falls within a different county.

- Specific states have some quirks in Helbock’s data when it comes to their counties: a) Hawai’i post offices are identified by island instead of county, and b) Alaska post offices do not include a county.

- Stamp Scarcity Index

- Helbock included a Stamp Scarcity Index score from 0-9 in his dataset to help stamp collectors: “Inclusion of a Scarcity Index (S/I) value for each post office listed herein is, far and away, the most arbitrary piece of information in the listing…The S/I value assigned to each post office is intended to reflect the relative scarcity of the most commonly occurring type of postmark for each office.”

- Miscellaneous:

- Helbock: “Post offices believed to have never been in actual operation, i.e., the so-called ‘paper offices’ have been omitted from the listing in cases where they have been identified as such. Many post offices listed in the “Records of Appointments of Postmasters” are noted to have been “rescinded”, rather than discontinued.”

- Helbock: “It does not include contract or classified branches, stations, or community post offices (CPO), even though some of these postal units have postmarked mail using their own name independently of their parent post office.”

Stage 2: Data Processing

Richard Helbock’s dataset contained a wealth of historical information. To turn it into a spatial dataset, it needed to go through a process of geocoding, or assigning geographical coordinates to each individual post office. Cameron Blevins refined this geocoding process between 2014-2021. A short summary of this process is below. A longer and more detailed description along with the code used by Blevins can be found in the US Post Offices Github repository.

Main Dataset: Geocoding using the GNIS Database

Blevins used a historical gazetteer approach based on the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) Domestic Names database collected by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names, under the U.S. Geological Survey. Blevins wrote a series of scripts in R that attempted to take the name, county, and state of a post office and look for a corresponding match in the GNIS dataset to find its geographical coordinates. Blevins’s GNIS geocoding process found geographical coordinates for 112,521 out of 166,140 post offices (67.73% of all the records). These coordinates can be found in the file: us-post-offices.csv.

Alternative Dataset: Semi-Random Coordinates

Is it better to have a map with some missing data or a map with some inaccurate data? This question led Cameron Blevins to create an alternative dataset in US Post Offices for visualization and illustrative purposes: us-post-offices-random-coords.csv. This includes semi-random geographical coordinates assigned to post offices that had not been geocoded using the GNIS database. This was made possible by the fact that Richard Helbock recorded information about the state and county of a post office. Even if we don’t know its exact location, we know the post office fell somewhere within a particular county’s borders. Blevins used county boundary shapefiles to generate a set of randomly distributed points within the borders of every county in the United States and then randomly paired those coordinates with post offices located within that county that had not been matched to a GNIS record. Although the specific locations of these post offices are incorrect, the potential error is constrained to a post office’s surrounding county - ie. a post office in Florida is not going to be located in Vermont, and a post office outside Los Angeles is not going to be placed near San Francisco. A longer and more detailed description of this process can be found in the README file for the US Post Offices Github repository.

How should I use this data?

Short answer: Carefully! :) Before using US Post Offices, read the following:

Understand the geocoding process and its limitations.

- If you are using

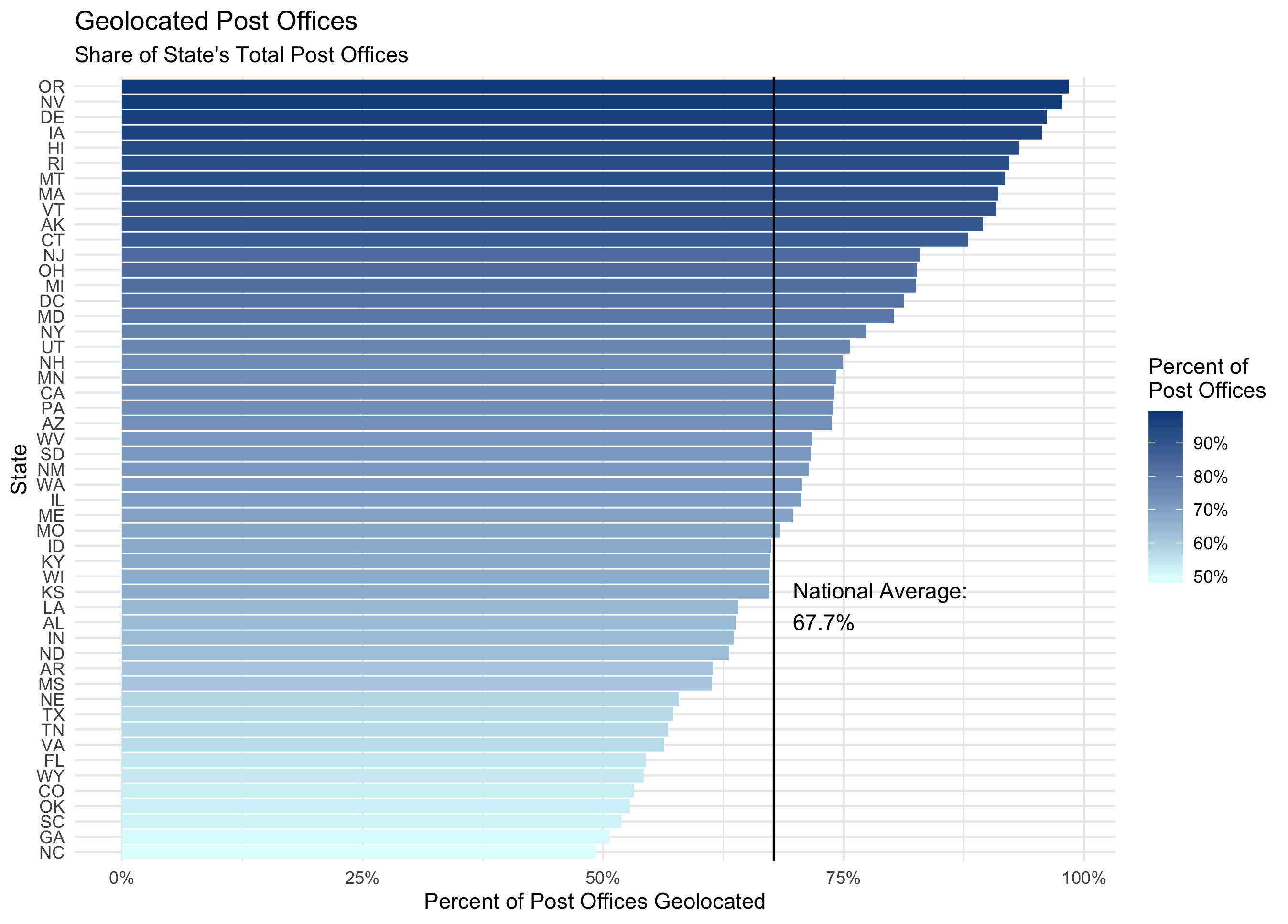

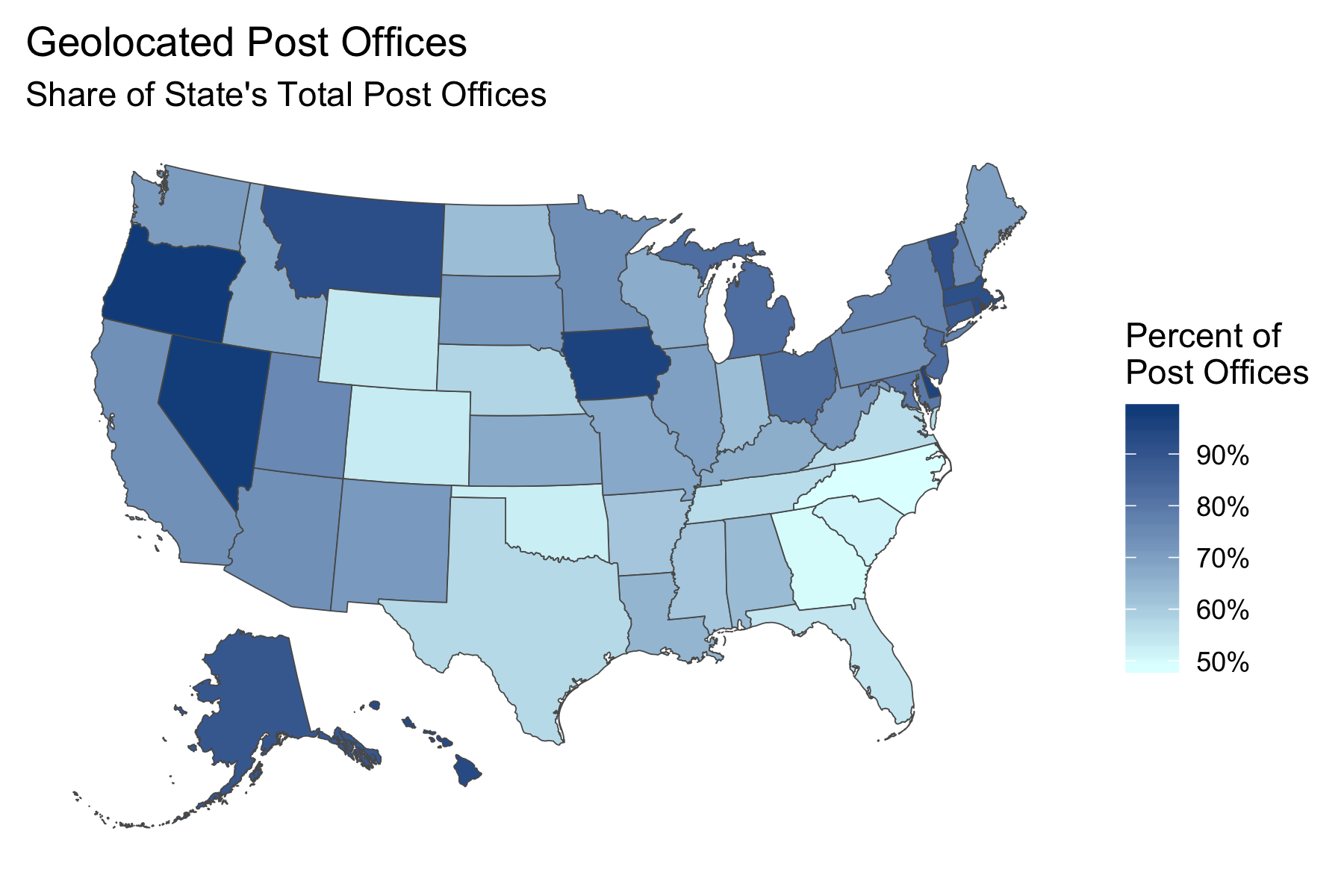

us-post-offices.csvto make a map of post offices it will NOT capture every single post office in operation. Many data points will be missing from the map. This is an obvious point, but it is arguably the most important one to keep in mind when working with this data. - There is wide geographical variation in how successful the geocoding process was for different parts of the country. Whether or not a post office could be geocoded was often dependent on how comprehensive the GNIS records were for its state. at the extremes, the geocoding process successfully found coordinates for 98.35% of Oregon post offices vs. just 49.32% of North Carolina post offices.

Percentage of a state's total post offices successfully geolocated using the GNIS database

Percentage of a state's total post offices successfully geolocated using the GNIS database

- Any maps made with

us-post-offices.csvwill display a larger share of the actual post offices in operation in areas like New England, the Midwest, and many parts of the the Far West (especially the Pacific Slope). Conversely, areas of the South and a few pockets such as Colorado, Wyoming, and Oklahoma will have a much lower proportion of their post offices displayed on a map.

Percentage of a state's total post offices successfully geolocated using the GNIS database

Percentage of a state's total post offices successfully geolocated using the GNIS database

- The geocoding success rate was not evenly distributed across the dataset. Post offices that were in operation for longer periods of time were more likely to find a match in the GNIS dataset than post offices that only existed for a short period of time. Post offices that were successfully matched in the GNIS database were in operation for an average (median) of 38 years. That number was just 5 years, on average, for post offices that did not have a match in the GNIS database. This makes sense. GNIS features were created by consulting historical records such as maps, and post offices that only existed for a short period of time appear in far fewer historical records. However, it also also means that any visualizations relying on geocoded coordinates in this dataset are going to be skewed towards more stable, long-lasting post offices and away from post offices that operated for a shorter period of time.

- Even those post offices that were successfully geocoded using the GNIS database may not have the right geographical coordinates. There are a scattering of false positives - ie. a post office that was matched to the wrong GNIS feature. As detailed in the README file for the US Post Offices Github repository, Blevins minimized false positives through a variety of steps, but there are undoubtedly a small number of post offices whose locations are incorrect. The error for these should be constrained to within the surrounding county, however.

- A post office’s geographical coordinates found through the GNIS geocoding process have varying degrees of precision. These records should not, for instance, be used to distinguish the location of a post office within a community, town, or city (ie. whether it was located on Main Street or First Avenue).

Decide which data file to use.

- There is a tradeoff between the two main data files

us-post-offices.csvandus-post-offices-random-coords.csvthat involves the issue of or precision vs. comprehensiveness. A map usingus-post-offices.csvshows only post offices that were successfully geocoded using the GNIS database, and has a relatively high degree of precision (each of the points on the map are probably located in the right spot) but lowerer overall comprehensiveness (there might be hundreds or thousands of missing data points). Conversely, a map usingus-post-offices-random-coords.csvshows all post offices from the dataset - including those with semi-random coordinates - and might be more comprehensive (there are no missing data points) but has a much lower degree of precision (some data points aren’t in the right location within a county). - To see this tradeoff between

us-post-offices.csvvs.us-post-offices-random-coords.csv, let’s take a look at Colorado in the year 1880. Colorado had one of the lowest percentage of post offices that were successfully geocoded using the GNIS database. This means that a map of its post offices will be missing a lot of data, giving an incomplete picture of the state’s postal coverage. One could argue that adding in the missing post offices usingus-post-offices-random-coords.csvcreates a more “accurate” overall picture of the extent of Colorado’s postal coverage in 1880:

The tradeoff between `us-post-offices.csv` vs. `us-post-offices-random-coords.csv`

The tradeoff between `us-post-offices.csv` vs. `us-post-offices-random-coords.csv`

- Each of the light blue points on the above map does not represent the precise location of a post office and is likely “off” by many miles. To drive this home, we can re-run the process of matching post offices with randomly distributed coordinates inside a county and then compare the results on a map. If we were to zoom out to a nation-wide map of the United States, it would be hard to pick up much of a difference. But zoomed in to a state level, the differences between two sets of semi-randomized points can be quite noticeable:

Two sets of semi-randomized coordinates for post offices that were not successfully geocoded

Two sets of semi-randomized coordinates for post offices that were not successfully geocoded

- For mapping purposes, you need to weigh the benefits and downsides of using an incomplete spatial dataset vs. one with semi-randomized locations for some of its records. If you are mapping zoomed-in areas or trying to show the exact locations of a specific set of post offices, consider using

us-post-offices.csvalong with an explanation of its missing data points. If you are mapping larger areas or and more general spatial patterns of coverage and extent, the individual errors of specific post office locations aren’t going to be as visible and you should consider usingus-post-offices-random-coords.csvwith an explanation of its semi-randomized coordinates.

Exercise caution when doing precise quantitative analysis.

- The limitations of this dataset make it much more effective for illustrative and visualization purposes than for precise quantitative analysis along its geographical and temporal dimensions. For instance, we might want to ask a spatial question such as: how far away was the average post office from a railroad line? But given how many post offices have either missing or inexact locations, this kind of analysis is thorny at best. The same goes for the temporal information captured in the Established, Discontinued, and Continuous fields. For instance, as outlined in the explanation of Helbock’s data collection steps above there are instances in which the post office’s discontinued year implies that it shut down when, in fact, it may have simply changed its name. Review these fields in the

us-post-offices-data-dictionary.csvto make sure you understand what each of these fields do and do not represent.

Remember that post offices are not a direct proxy for population.

- It is tempting to see a post office as a spatial proxy for a surrounding community. And to some degree, this is true: the presence of a post office does indicate that a group of people was living nearby. But the inverse is not true: the absence of a post office does not mean that there was nobody living in that area. In fact, through the late 1800s the absence of post offices often indicated the presence of Indigenous groups that either blocked settler expansion or that suffered from a lack of postal coverage within the borders of government reservations.

This map shows the relationship between Native land, government reservations, and postal expansion.

This map shows the relationship between Native land, government reservations, and postal expansion.

- A post office says nothing about the number of people it served: the New York City post office looks identical on postal maps to a small rural post office serving a fraction as many people. If you’re looking for data about the historical populations of US towns and cities, you should use a source such as the Alperin-Sheriff/Wikipedia Population dataset.

- The relationship between a post office and a surrounding population changed over time. A post office in 1850 was not the same as a post office in 1950. In particular, the rollout of Rural Free Delivery in the early 20th century caused a wide-scale consolidation in the network. This new service meant that rural residents went from fetching their mail at the local post office to having it delivered to their doorstep, which caused the closure of thousands of post offices. This did not indicate that people were moving away from those areas; it was simply that fewer post offices could now serve a larger surrounding area.

Rural Free Delivery (officially instituted in 1902) caused the closure and name changes of thousands of post offices.

Rural Free Delivery (officially instituted in 1902) caused the closure and name changes of thousands of post offices.

Where do I access the data and how is it stored?

You can download the US Post Offices dataset through its Harvard Dataverse record: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NUKCNA. Cameron Blevins decided to use Harvard Dataverse as a standardized repository for data sharing, archiving, and citing. You can also access the data along with accompanying code used for the geocoding process in the US Post Offices Github repository.

How should I cite the data?

If you use the dataset, please cite the Harvard Dataverse record:

How has this data been used?

The following publications use US Post Offices:

- Cameron Blevins, Paper Trails: The US Post and the Making of the American West (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021).

- Cameron Blevins, Yan Wu, and Steven Braun, “Gossamer Network” (2021).