Postal Geography and the Golden West

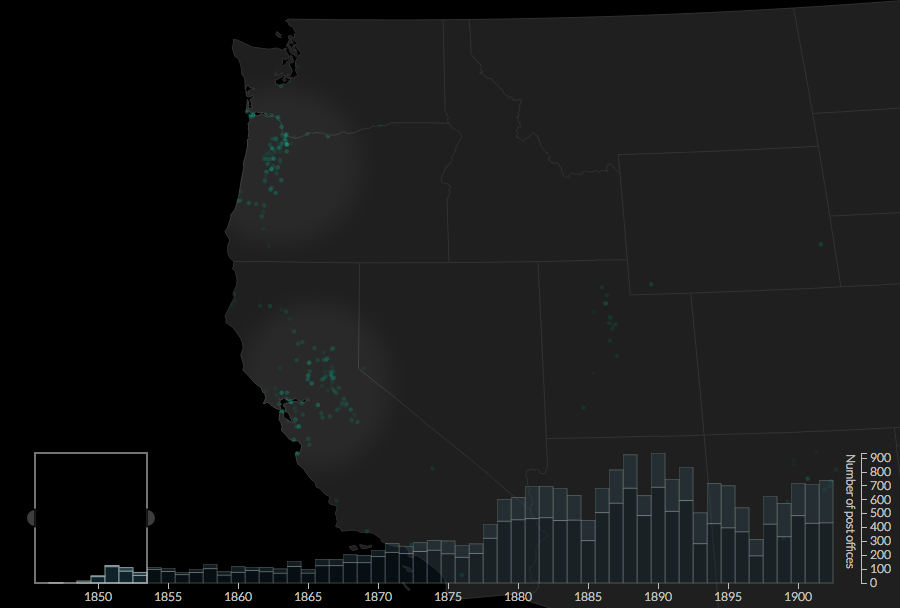

I want to tell you a story. It’s a story about gold, the American West, and the way we narrate history. But first let me explain why I’m telling you this story. I’m in the midst of writing a dissertation about how the U.S. Post shaped development in the West. The project is a work of geography as much as history. It traces where and when the nation’s postal network expanded on its western periphery, and part of these efforts include collaborating on an interactive visualization that maps the opening and closing of more than 14,000 post offices in the West. The visualization reveals the skeleton of a “postal geography” that bound Americans into a vast communications network. It's a powerful research tool to explore spatial patterns spread across fifty years, thousands of data points, and half of a continent. Visit the site and read more about the visualization. But first, I want to use this tool to tell you a story.

Cameron Blevins and Jason Heppler, Geography of the Post

Cameron Blevins and Jason Heppler, Geography of the Post In the beginning there was gold...

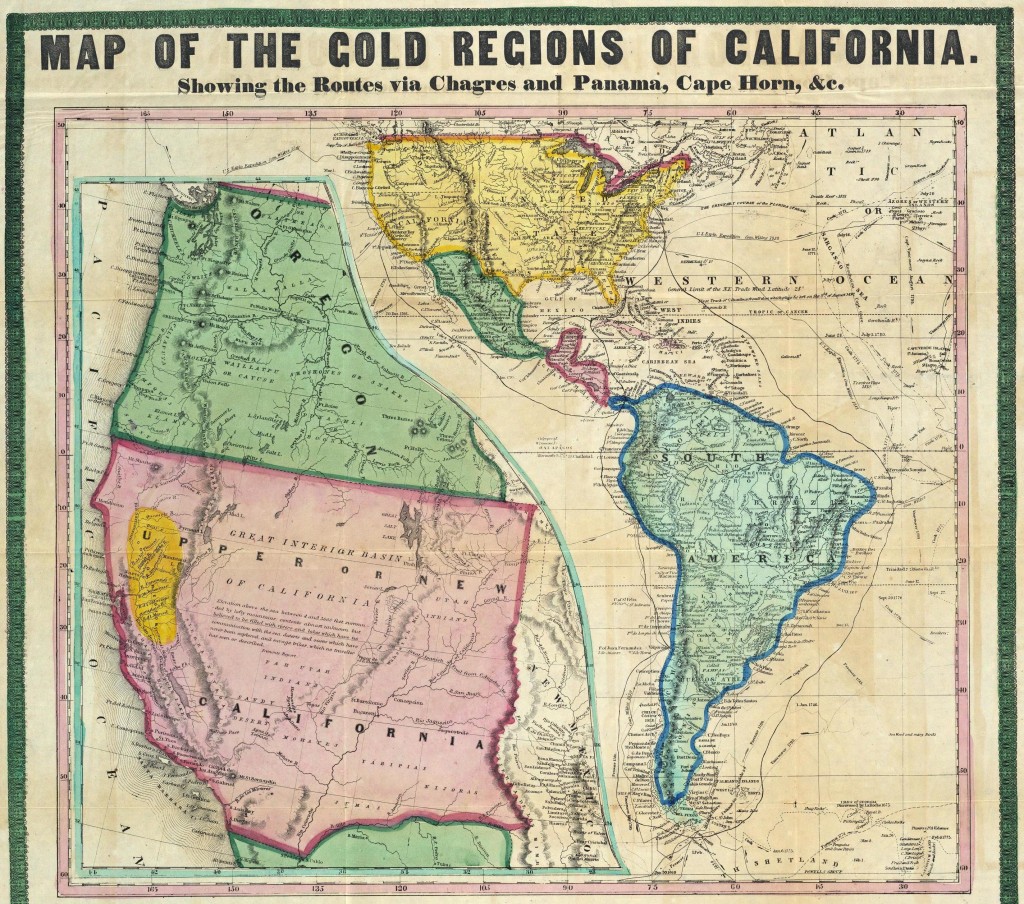

That’s usually how the story of the West starts: with a gold nugget pulled out of a California river in 1848. The discovery of gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills set off a global stampede to California and pulled the edges of American empire to the shores of the Pacific.

The California Gold Rush casts such a dazzling light across western origin stories that it’s often hard to see past it. But there was more than just gold. Even as miners flocked to the Northern California, farmers were plowing fields up and down Oregon's Willamette Valley. But whereas gold is exciting, farmers are boring. They’re pushed aside in gilded narratives about the West. When Oregon farmers do appear, they serve as an epilogue to a much more exciting story about covered wagons, dusty trails, and Indian attacks. As soon as overland emigrants traded in their covered wagons for seeds and ploughs they're pushed to a dimly lit corner of western history.

But these women and men nonetheless left their mark on the geography of the West. Even as they raised their barns and planted their fields they participated in a long-standing American tradition of demanding that the U.S. government bring them their mail. Each new Oregon town came with a new post office, and five years after the discovery of gold in California there were nearly as many post offices in Willamette Valley as there were in the mining region of the Sierras. In most historical accounts the blinding glitter of California gold has rendered these Oregon settlements all but invisible. Our story pulls them out of the shadows.

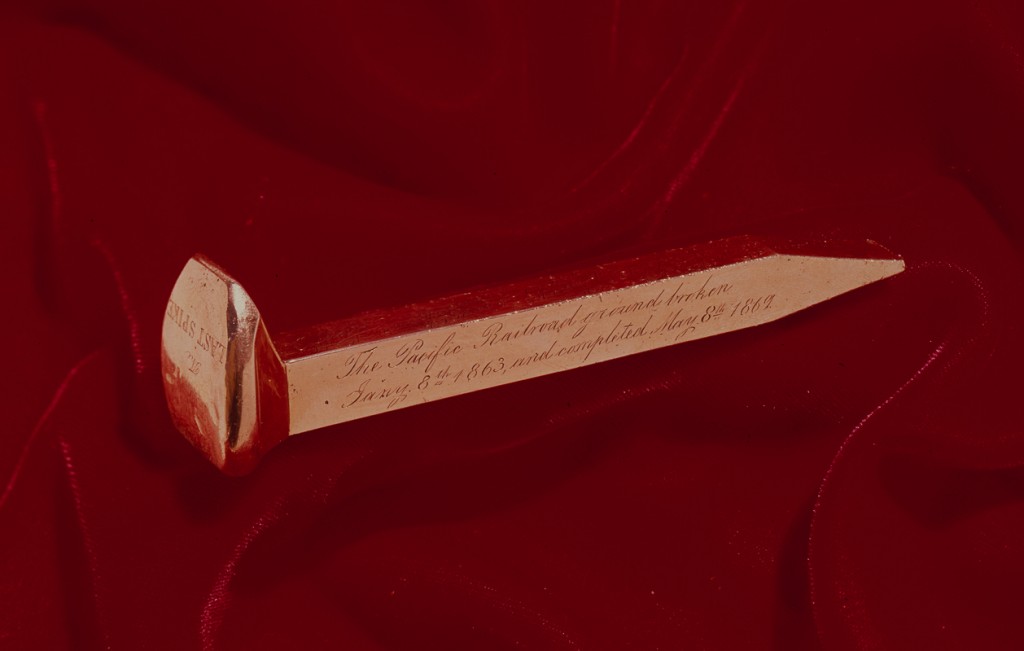

Gold survived in stories about the West long after it ran dry in California’s mines. In May of 1869 a ceremonial golden railroad spike shimmered in the sun at Promontory Point, Utah. It was the “last spike” that would symbolically link the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads, completing the nation’s first transcontinental railroad. The ceremony concluded six years of breakneck labor that laid down more than a thousand miles of wood, metal, and stone across the West. The golden spike at Promontory Point proved just as momentous as the gold flakes at Sutter’s Mill two decades before, inaugurating a new era of western settlement. And, just like the gold rush, the dramatic glare of the golden spike blinds us to other stories.

You can be forgiven for thinking that the rest of the West stood still while workers laid down transcontinental railroad tracks in the late 1860s. That is, after all, how stories of the West are often told. But the West wasn’t standing still. A simultaneous story was taking place in southwestern Montana, where the discovery of gold led to a new rush of Anglo settlement into the region. By 1870 this mineral-fueled migration had transformed western postal geography as much as the transcontinental railroad tracks that snaked through northern Nevada, Utah, and southern Wyoming. As miners and speculators streamed into Montana they dragged the nation’s postal network with them. Whether established at a Montana mining camp or a Nevada railroad depot, the post offices that appeared during these years reflected two stories occurring simultaneously, of a prospector shivering in a cold mountain stream and a railroad worker sweating in the desert sun. Yet we tend to separate their labor when we narrate the history of the West; the miner waits offstage for the railroad worker to finish laying down tracks before he wades into the Montana stream. Anchoring them to a larger spatial network recovers the simultaneity of their stories.

Blank spaces are foundational for the stories we tell about the West. In the worst of them, white settlers carry the mantle of American civilization into an empty western wilderness. It’s a story that systematically writes out the presence of non-Anglo settlement. Using postal geography to narrate western history runs the risk of parroting this story. After all, post offices on a map resemble nothing so much as pinpricks of light filling in the region’s dark blank spaces. But those blank spaces also have the potential to tell a very different kind of story.

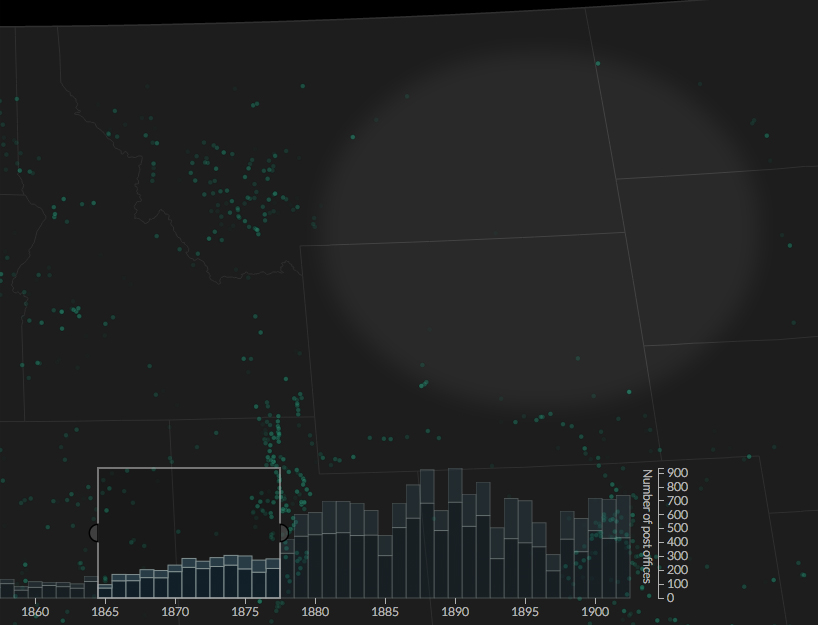

During the late 1860s miners in Montana and railroad workers in Nevada were joined by another migration into the region: soldiers marching into northern Wyoming and southern Montana to battle a coalition of Lakotas, Northern Cheyenne, and Northern Arapaho. After suffering repeated losses, the U.S. Army withdrew from Powder River Country and signed a peace treaty in 1868 that ceded control of the area. Unlike the miners and laborers, these soldiers left no trace on the U.S. postal network: the Powder River Country remained utterly devoid of post offices for the next decade.

Silence speaks volumes in the stories we tell. In our story the blank spaces in the postal network act as narrative silence, laden down with meaning. The map's negative spaces have as much to tell us as its constellations of post offices. It is a story about the control of space. Post offices were a marker of governance, a kind of lowest common institutional denominator. The absence of a post office signaled the lack of a state presence. In this context, the yawning blank area in northern Wyoming and southern Montana reflected the tenuous position of the U.S. Government in the West. Through the late 1870s vast swathes of the West remained outside the boundaries of American territorial control and solidly within the sphere of native groups. The government's inability to extend the U.S. Post into this region defined the geographic limits of westward expansion. Anglo-American settlement wasn’t inexorable and it didn’t unfurl in a single unimpeded wave. It occurred in fits and starts, in uneven forays and halting retreats. It’s a narrative whose boundaries were drawn by the supposedly blank spaces of the West and the people who lived in them.

Our story ends where where it began: with gold. In 1874 an expedition led by George Armstrong Custer marched into the Black Hills in present-day South Dakota. Their announcement that they discovered gold touched off a frenzied rush into an area that was officially outside the control of the the United States government. Clashes between prospectors and Indians escalated over the following year, eventually erupting into all-out warfare between the U.S. Army and the Lakotas and Cheyennes in early 1876. Despite the 7th Cavalry's dramatic defeat at the Battle of Little Bighorn, the U.S. Army ultimately prevailed. The end of the campaign in 1877 and the dissolution of the Fort Laramie Treaty unleashed a flood of white emigrants into the gold fields of the Black Hills. A dense pocket of post offices appeared almost overnight to bring the mail to these gold-hungry settlers.

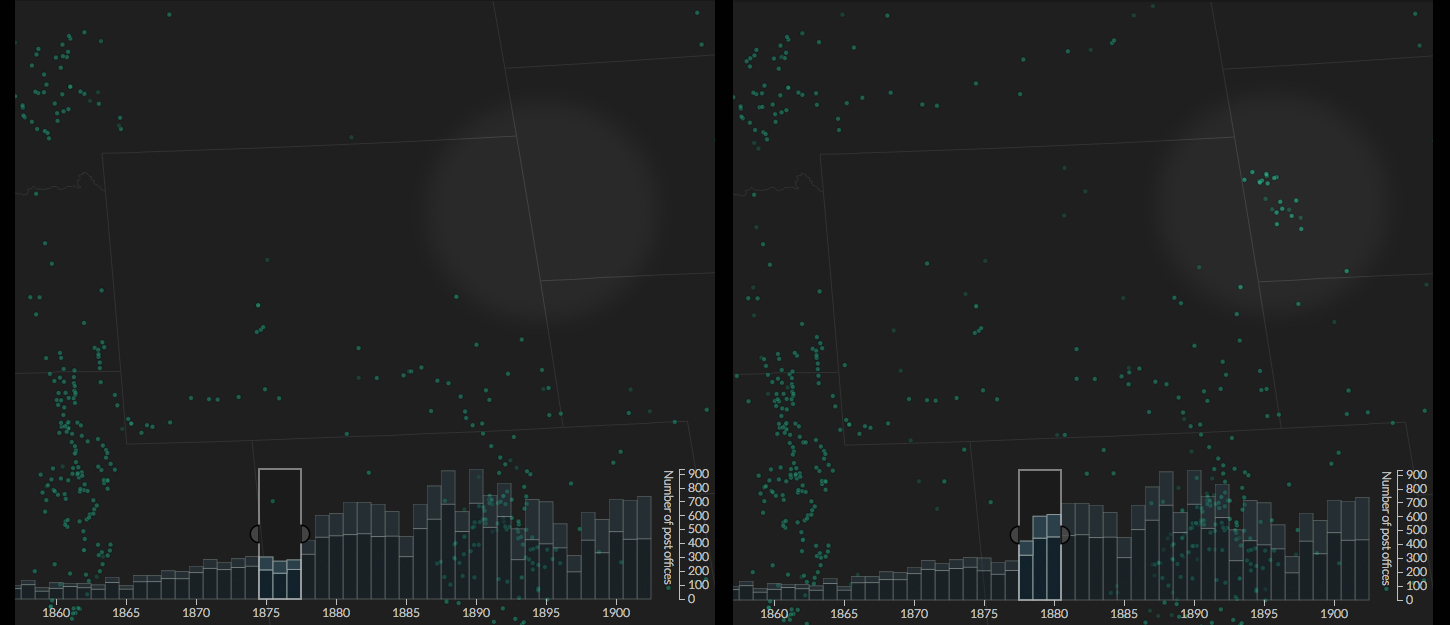

Left: U.S. Post Offices, 1875-1877

Left: U.S. Post Offices, 1875-1877 Right: U.S. Post Offices, 1878-1880

The image of post offices twinkling into existence in the Black Hills says nothing about the violence that birthed them. Their appearance depended on a military campaign and the ultimate removal of people whose very presence had visibly defined the limits of American territory. But these post offices nevertheless help us to tell a different kind of story about the West. It’s a story that expands our vision to look beyond the glare of the California gold rush and towards the plowed fields of Oregon. It’s a story marked by simultaneity, a story about railroad workers swinging sledgehammers in northern Nevada even as prospectors panned for gold in southwestern Montana. And it’s a story about blank spaces and the people and meanings that filled them, a story about the control of space and the boundaries of western expansion.