One last lecture…

On Wednesday I taught my last class of the spring semester for my undergraduate-level course History of the Western United States. When I was preparing for the class, I kept experiencing that nagging worry that, for most of my students, this was the last history class they’d ever take. So I decided to do “one last lecture” on a basic question: what did I want them to remember from this class? As I tried to answer this question, I found myself moving further and further away from the subject of the course, and more and more towards a broader plea for the relevance of history as a way of thinking. Forcing myself to articulate that relevance was a really helpful process, so I thought I would post the notes to this lecture here.

This might be obvious, but I should note that the following was not intended to be read on a webpage. This is intentional: one of the other reasons for posting this was that I want to pull back the curtain and show a real-life example of lecture notes. When students give presentations, I often find myself giving them the same sort of feedback about the differences between writing for someone to read versus writing for someone to listen (a paper versus a presentation). What follows is a very lightly edited version of my lecture notes from class on Wednesday, along with accompanying slides. Although it’s more formal and closer to written prose than many of my lectures, it’s still a challenge to scroll through online. There are repeated words and passages, sentence fragments, and course-specific references that are hard to follow for someone who hasn’t sat in my class for the past sixteen weeks. That’s kind of the point. I’m hoping all of this illustrates that difference between writing to read versus writing to listen.

One Last Lecture…

- A few of you are history majors, but I know for the majority of you, this is probably the last history class you’ll ever take.

- Which is a lot of pressure for me.

- This is it!

- the last shot I’ve got for you to remember me.

- Now I should clarify that I don’t actually care if you remember ME, specifically,

- me as a person or even me as a professor.

- Feel free to immediately forget every detail about me.

-

But what worries me is that this class becomes one of those classes you immediately forget

- a class that just kind of runs together with the dozens of other classes you took at Northeastern.

- So on that note, I want you to take that index card and write down one thing you’re going to remember from this class.

-

Five years from now, what are you going to remember? This can be anything you want: - a big theme or topic - an assignment or activity - A lecture or a story - A factoid, person, event, whatever you want …

- I’m doing this partly because I’m curious what you find most memorable.

- But I’m also doing this because I want you to, in fact, remember this class.

- That could be the content of the course, and I’m certainly hoping you learned new things about the western United States.

- But in another sense, I don’t actually care that much about the nitty-gritty details of the content, either.

- I don’t care whether five years from now you remember the Battle of Glorietta Pass

- Or, to use an example of something I messed up earlier this semester - whether it was James Marshall or John Marshall who discovered gold at Sutter’s Creek

- I’m guessing none of you are going to become a historian.

- But whatever career or life path you end up choosing, I hope that you remember some of the core principles of historical thinking that we’ve talked about over the past couple of months

- I hope you come away from this class with a curiosity about the past

- The relationship between geography and history

- A thoughtfulness about myth, memory, and history

- And above all, an appreciation for how the past continues shapes the present …

- So why do I think you should you remember this class?

- The answer has very little to do with what happened a hundred years ago in the West

- And everything to do with the present world we live in today

- To try and drive home what I mean by that, I’m going to look at an event from the present-day

- this particular event happened five days ago

- right across the Charles River, just a few miles away

- I want to look at this event to show you why history is so important

- Last Friday night, several Cambridge Police officers responded to multiple calls

- that a naked man was wandering down the middle of Mass Ave

- he was acting erratically, and had thrown his clothes at a woman

- After confronting the man and talking to him for several minutes,

- eventually the man in question approached one of the officers

- Which led a second officer to tackle him to the ground,

- He struggled, they try to restrain him, and

- During this struggle one of the officers punched the man four or five times in the stomach

- They subsequently arrested him and charged him with “indecent exposure, disorderly conduct, assault, resisting arrest, and assault and battery on ambulance personnel”

- It turned out this man, Selorm Ohene

- is a black mathematics major at Harvard,

- and news outlets across the country have picked up the story

- So how does studying history help us understand what happened last Friday night?

- I know you’re sick and tired of seeing this slide by now,

- But I show it so many times for a reason

- History is an act of interpretation

- I mean this on two different levels

- First, on a basic level, we need to interpret what actually happened that night

- If we treat this as a historical event, we need to get the details of what happened

- the who, what, when, and where

- Which, as you’ve hopefully learned in this class,

- Is never as easy as it might seem

- It requires you to look at as many different sources as you can

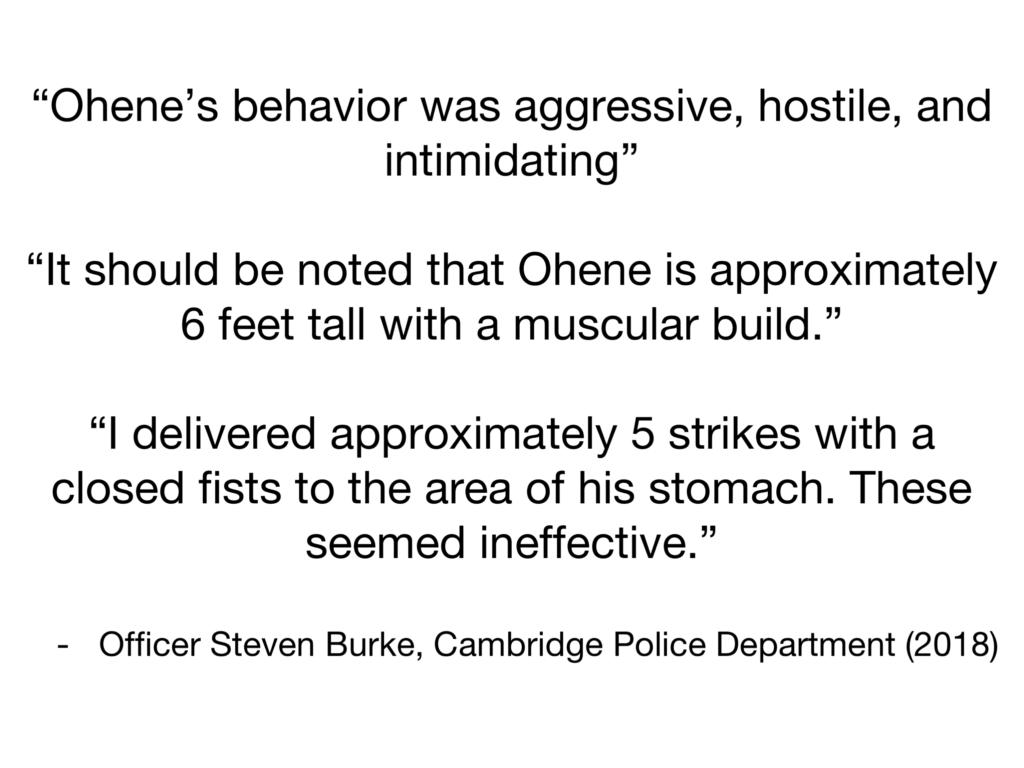

Cambridge Police Department Report

Cambridge Police Department Report

- For this particular event,

- we might read the police report filed by one of the officers

- It says how they interviewed two of the student’s companions, who said that Ohene might have ingested hallucinogens, which could explain his erratic behavior

- And goes on to say:

- “As Ohene [the name of the student] and I conversed, I observed him clinch both his fists. Ohene started to take steps towards officers in a an aggressive manner. I perceived this as a threat and thought an attack was imminent.”

- It goes on to say, “We gave Ohene verbal commands to give us his hands which he did not. Unable to pry Ohene’s hands from underneath his body, I delivered approximately 5 strikes with a closed fists to the area of his stomach.”

- But as we’ve learned, we can’t rely on just one source

- Especially one that is narrating an event from a single perspective

- Fortunately for future historians studying 2018

- Cell phones are everywhere

- Which meant that onlookers actually took several videos of the event

- In this case, we’d want to look at these videos to try and piece together the details of what happened

- This is really no different from the kind of analysis you’ve done in this class

- A cell phone video or a police report - these are primary sources

- Think about the maps of New Spain that you looked at, that had no idea what was in the interior of the West

- Or anti-immigrant political cartoons

- Or, perhaps most relevant, first-hand accounts of the events at Sand Creek

- Historical thinking forces you to look at these kinds of sources critically

- to try and take into account not only what it says,

- but also who made it

- under what conditions

- from what perspective

- and for what audience

- What are these sources missing?

- What are their limits?

- Again, these are crucial skills not just for understanding something that happened a hundred years ago, but for understanding something that happened RIGHT NOW, a few miles away, in 2018.

- The second kind of historical interpretation involves getting beyond this basic level of what happened

- Because understanding the past is not just collecting facts, dates, and names

- You have to piece them together into a larger narrative or interpretation in order to understand the significance of these kinds of events, why they matter and how they fit together.

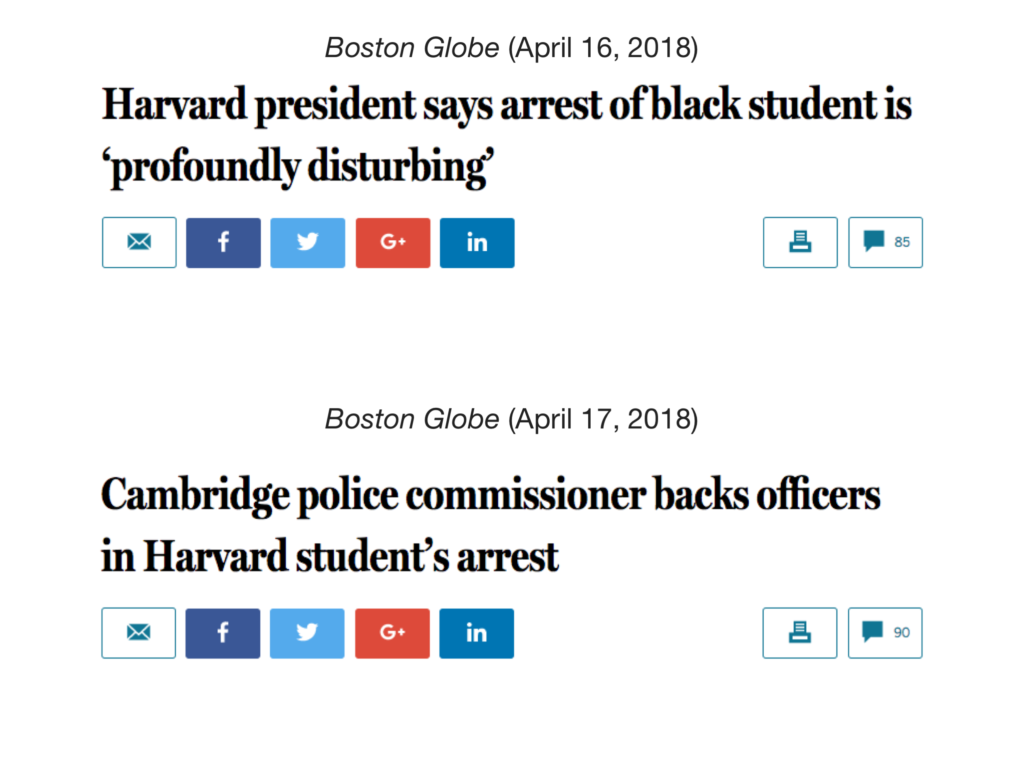

- In the last couple of days, two competing narratives or interpretations have emerged about last Friday’s arrest

- On Sunday, the president of Harvard, again, the school where this man was a student

- Called the incident “profoundly disturbing”

- Activists have taken it up as an example of police brutality and the kind of racism that infects our criminal justice system

- On the other side of the ledger,

- the Cambridge police commissioner held a press conference on Monday

- where he expressed his full-throated support for the officers in question

- saying they were simply taking actions to protect bystanders, themselves, and the man himself

- Again, two conflicting interpretations not necessarily of the details of what happened,

- but of the meaning and significance behind it

- If we think of this event as historians, we need to evaluate both of these interpretations

- To do that, you have to use that other skill that I keep yammering on about: historical empathy

- the ability to put yourself in the shoes of the people who lived in the past and see the world through their eyes

- I would argue that that if you can pull off historical empathy

- of understanding how the world looked through the eyes of a person who lived a hundred years ago

- a world that is was so incredibly, radically different from our own

- If you can do THAT, then you’ll be better equipped to put yourself in the shoes of someone living today

- Let’s go back to the interpretation put forward by the Cambridge police commissioner

- Empathy forces us to take his interpretation of the events seriously.

- So let’s think about it from the perspective of one of his officers who was there

- There’s a naked man wandering in the middle of a busy street

- He’s incoherent and behaving erratically,

- He’s thrown his clothes at someone

- And you’ve received six different 911 calls

- So on a basic level, you can understand why they might have approached the situation with a certain degree of caution and suspicion

- More broadly, though, that skill of empathy involves understanding the CONTEXT of an event

- In the case of last Friday’s arrest, there might have been other reasons why the officers decided so quickly to resort to force

- In fact, just one day before the event a police officer in Yarmouth, Massachusetts, was killed while serving an arrest warrant

- I can’t know for sure, but these Cambridge police officers were probably aware of this

- Because the wider law enforcement community across Massachusetts had been offering their condolences to the officer’s family for the past 24 hours

- Perhaps they had this event on their minds,

- perhaps they were thinking about their own families

- maybe all of this put them on edge when they arrived at the scene last Friday night

- This is what I mean by context

- But historical empathy does not mean that all narratives and all interpretations are somehow equally valid

- It’s not just trying too see both sides and leaving it there

- At some point, you’ve got to choose an interpretation based on the information, the context, and your own analysis

- In this case, my own interpretation falls a lot closer to the other side of the ledger

- The one that sees this event as “profoundly disturbing”

- The reason for this is that this event is not taking place in a vacuum

- When police officers use violence against a black man

- It is deeply entangled within a national conversation that has emerged over the past few years

- The Black Lives Matter movement

- That has called attention to a recurrent pattern of police violence against people of color

- It’s a conversation that was sparked by the killing of Michael Brown at the hands of a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014

- Followed in short order

- …by the killing of Eric Garner in New York City

- …and Tamir Rice in Ohio

- This isn’t some recent phenomenon

- It’s part of a much longer history

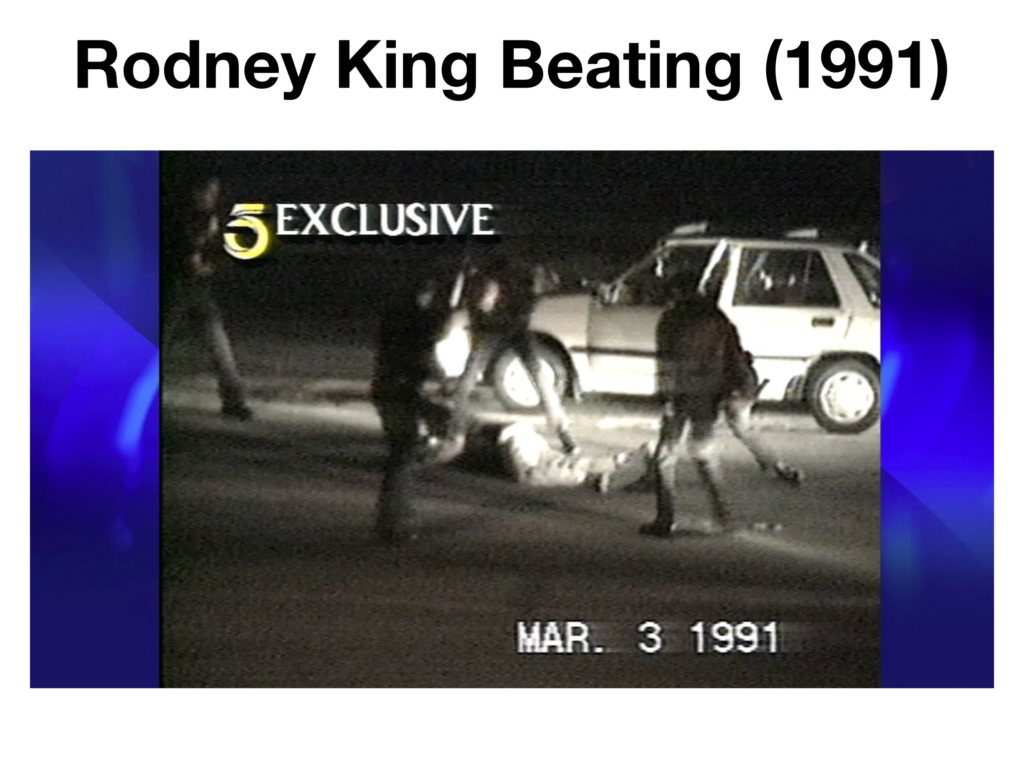

- Last Friday’s events call to mind Rodney King,

- a black taxi driver in Los Angeles who was pulled over in 1991

- and severely beaten by members of the LAPD

- Despite the fact that it was captured on video…

- A jury acquitted the officers in question

- All of which ties into an even longer pattern in this country

- Of Americans seeing black men

- As violent

- As dangerous criminals

- or even animals

- You can see this if you start using another one of those historian’s skills

- the close reading and analysis of sources

- And apply those skills to the grand jury testimony of the white officer who killed Michael Brown

- You can see how he described the eighteen-year-old in precisely these kinds of animalistic, violent terms

- Testifying that:

- “I’ve never seen anybody look that, for lack of a better word, crazy. I’ve never seen that. I mean, it was very aggravated…aggressive, hostile.”

- He “had the most aggressive face. That’s the only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon, that’s how angry he looked.”

- And finally, when he explained why he shot Michael Brown no fewer than twelve times

- he explained it was because the teenager seemed unstoppable, that “it looked like he was almost bulking up to run through the shots”

Cambridge Police Department Report

Cambridge Police Department Report

- Again, applying those close reading skills to another document

- The police report from this past weekend

- You can see parallels in how the officer describes the Harvard student Selorm Ohene

- Aggressive, hostile, intimidating

- Calling attention to the student’s physicality, that he was muscular

- And how he didn’t even seem to feel pain

- This language fits within a larger pattern in which Americans of all stripes and political persuasions see black men as threatening and dangerous

- This is partly what I mean by the need to understand a larger historical context

- But to understand events, you also have to understand the local history of individual places

- Remember that one of the themes of this class was the relationship between history and geography

- How local context shapes the history of particular places

- Think back to that exercise you did near the beginning of class,

- using crayons to draw that caricatured View of the World from Northeastern University

- Part of the reason why I had you do this

- Was that it forces you to think about the perspective of how the world looks from a particular place

- And if you look at the world from the perspective of Boston

- you start to understand the importance of this local context behind last Friday’s event

- Just this year, a Boston police officer shot an African immigrant driving an ATV

- It turned out that the officer had a long history of making racist posts on online message boards under the screen name, and I swear I’m not making this up, “Big Irish”

- Or the case of another Boston police officer who was convicted of racially motivated violence in 2015

- when he drunkenly attacked his Uber driver

- shouting racial insults as he did so

- Or go back a few more years, to 2009, and to Cambridge itself, not all that far from where this student was arrested last Friday

- In 2009 a black Harvard professor named Henry Louis Gates Jr.

- had forgotten his keys and accidentally locked himself out of his house

- When he tried to get back in

- a neighbor called the police because she saw a black man robbing a house

- A Cambridge police officer arrived at the scene, got into a confrontation with Gates, and led him off in handcuffs

- Again, this is a nationally respected professor at the most famous university in the country

- Arrested for breaking and entering into his own home

- Of course, after this event happened,

- yet another police officer in Boston sent an incredibly racist email about Professor Gates

- Before claiming that, quote, “I am not a racist”

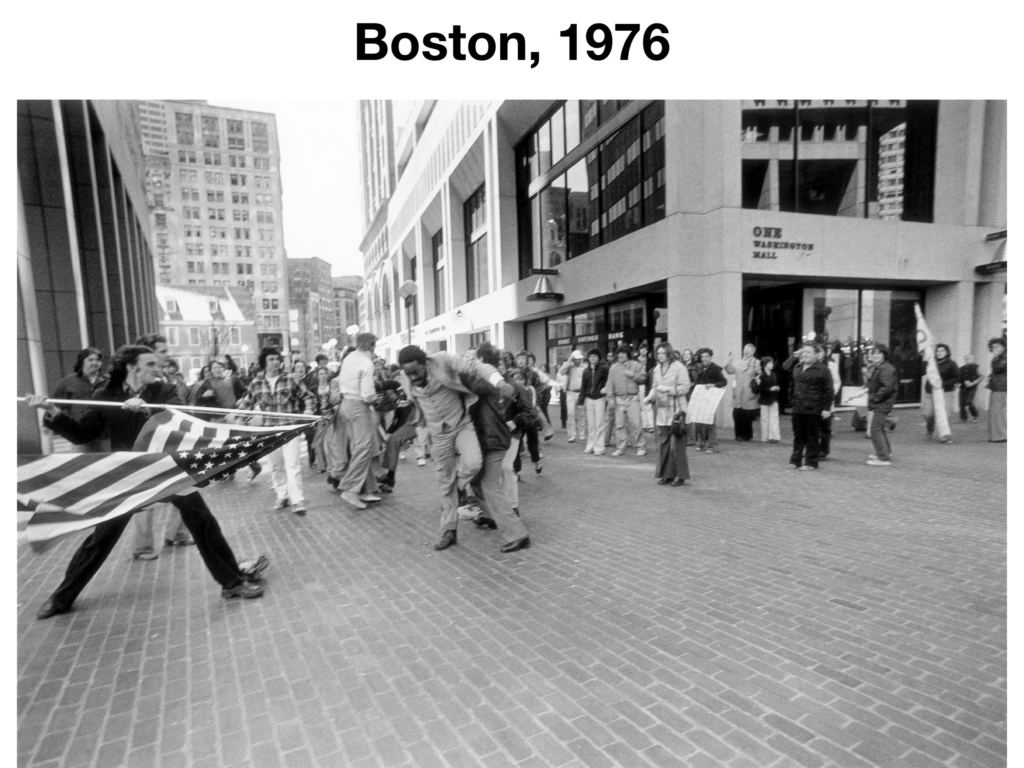

- Or we can go back even further, to the 1970s

- When white Bostonians became enraged after the city instituted bussing to bring black students to largely white schools

- to try and desegregate the city’s school system

- Leading to this famous photograph of a white Boston man attacking a black civil rights leader with an American flag, near the steps of city hall

- All of this calls to mind that William Faulkner quote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

- Everything has a history

- And while not all of that history is equally important for understanding the present

- Part of why we study history is to figure out which parts of it matter and how they all fit together

- In the case of the police violence last Friday against the black student in Cambridge

- I would say that all of this history that I just showed you, it does matter.

- Applying historical thinking to this event is what allows us to understand it better

- To interpret the event, not only in terms of what happened but how it fits into a larger context

- To see it not as some isolated, present-day event

- But as part of a larger historical narrative

- a larger historical structure

- If you remember nothing else from this class, I want you to remember this

- That history is not neutral

- it’s not simply stuff that happened

- it’s not dead

- History is a living, breathing thing

- The past exercises enormous power over the present, over our world today

- To understand this present world

- it’s absolutely crucial that we understand that power

- And THAT is why I want you to remember my class.