Getting Under the Hood of Graduate Coursework

As part of Stanford’s history graduate program, those of us studying the United States participate in a series of courses called “the core.” This consists of six courses taught by six different professors that cover the chronology of the United States - two each for (roughly) the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. On Stanford’s quarter system, this works out to three “core” classes each year that comprise the backbone of the Americanist graduate training. Having completed half of the core, I thought it would be interesting to take a look at its content.

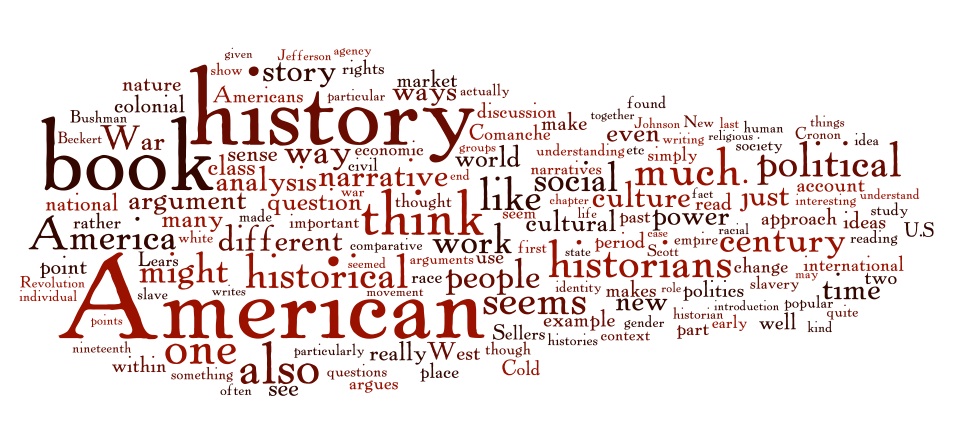

Each course follows a similar format: one book assigned each week, usually accompanied by additional excerpts or chapters of other books and related essays. The class posted short responses/questions which we then discussed in our once-weekly class. Even with a small class (around 8-12 students), the aggregate of our short responses produced a sizable body of text over the course of the year. The responses also offer a means of gleaning some of the overarching themes of US historiography. As Julie Meloni describes in a post at ProfHacker titled “Wordles, or the gateway drug to textual analysis” word clouds are an easy and playful way to visualize these themes:

Many of the words are not particularly surprising (American, history, and book, for example), but the word cloud does point towards the essence of Stanford’s “core” in training its graduate students to analyze texts from a largely historiographical standpoint. There are relatively few content words - Vietnam doesn’t appear too often, for instance. Instead, words such as analysis, argument, and narrative crop up in our responses. We are being trained to read a book not for its factual information but in order to evaluate its interpretive arguments. This is a crucial difference that often gets overlooked by those outside the profession, and this characteristic displays itself quite clearly in our responses.

Many of the words are not particularly surprising (American, history, and book, for example), but the word cloud does point towards the essence of Stanford’s “core” in training its graduate students to analyze texts from a largely historiographical standpoint. There are relatively few content words - Vietnam doesn’t appear too often, for instance. Instead, words such as analysis, argument, and narrative crop up in our responses. We are being trained to read a book not for its factual information but in order to evaluate its interpretive arguments. This is a crucial difference that often gets overlooked by those outside the profession, and this characteristic displays itself quite clearly in our responses.

Examining the central books that were assigned in the core gives a glimpse into what our professors thought were the important works in United States historiography. What follows are the major weekly books, in order of publication date:

| Patricia Limerick | The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West |

| Gordon Wood | Radicalism of the American Revolution |

| Charles Sellers | The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815-1846 |

| William Cronon | Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West |

| Richard Bushman | The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities |

| Robin Kelley | Race Rebels : Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class |

| Christine Leigh Heyrman | Southern Cross: The Beginnings of the Bible Belt |

| Amy Dru Stanley | From Bondage to Contract: Wage Labor, Marriage, and the Market in the Age of Slave Emancipation |

| Kristin Hoganson | Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars |

| Walter Johnson | Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market |

| Ann Fabian | The Unvarnished Truth: Personal Narratives in Nineteenth-Century America |

| Mary Dudziak | Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy |

| Elizabeth Anne Fenn | Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82 |

| Sven Beckert | The Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850-1896 |

| Caroline Winterer | The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780-1910 |

| Paul E. Johnson | Sam Patch, the Famous Jumper |

| Steven Hahn | A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration |

| Jeremi Suri | Power and Protest: Global Revolution and the Rise of Detente |

| Mae Ngai | Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America |

| Louis S. Warren | Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody and the Wild West Show |

| Susan Scott Parish | American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World |

| Charles Postel | The Populist Vision |

| Annette Gordon-Reed | The Hemingses of Monticello |

| Pekka Hamalainen | Comanche Empire |

| Jackson Lears | Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877-1920 |

| Peggy Pascoe | What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America |

| Susan Carruthers | Cold War Captives: Imprisonment, Escape, and Brainwashing |

Taking a look at all twenty-seven books reveals some interesting characteristics. Unsurprisingly, the assigned readings are heavily weighted towards recent work:

Part of the purpose of Stanford’s core is to develop a strong working knowledge of the issues and debates of the field. For example, Charles Postel’s The Populist Vision, published in 2007, takes on interpretations advanced over the past half-century that characterize the 1890s People’s Party as quixotic and backwards-looking. Instead, Postel argues that the movement was deeply committed to ideals of modernity and progress. The Populist Vision serves as an exemplary book to assign in the graduate “core” in part because it provides a strong background for the ongoing issues, debates, and trends of how historians have interpreted late nineteenth-century American politics.

Looking at the authors themselves is also interesting. The gender breakdown is quite even, with fourteen male authors and thirteen female authors. What I decided to examine was not just who these people were, but where they received their historical training. The twenty-seven different authors received their PhD’s from only ten different schools:

Columbia University Harvard University Princeton University Stanford University University of California, Berkeley University of California, Los Angeles University of Helsinki University of Leeds University of Michigan Yale University

In short, it’s a narrowly “elite” bunch. Eleven (over 40%) of the authors received their PhDs from Yale alone. Of the eight American schools represented, all of them currently reside in the top ten of US News and World Report’s list of history graduate programs. Of note, the authors had a more diverse background in both their undergraduate education (ranging from Montana State University to SUNY-Empire State) and the schools at which they currently taught. The prestige factor seemed to be most dominant at the graduate level.

The over-representation of elite schools highlights the stratified nature of graduate training in the American historical profession. I don’t mean to draw broad conclusions from an obviously limited and biased sample, which only reflects the decisions of three Stanford professors as to what they think are the most important recent books in the field. Yet the authors of these books were overwhelmingly trained at prestigious, “top-tier” programs. Does this mean that the products of Harvard and Yale’s programs are the only historians who received the quality training needed to write ground-breaking scholarship? Absolutely not. But the above reading list does imply that where a historian received their graduate education seems to have an outsized ripple effect on the reception and impact of their scholarship.