Generative AI and History in 2025

If you’ve followed debates around generative AI, you’ve probably seen the dismissal of Large Language Models (LLMs) as nothing more than “autocomplete on steroids”. This line of critique isn’t just about how the technology works; it’s an implicit claim about what it can produce. The idea is that because LLMs are just predicting sequences of words, all they can generate is plausible-sounding, mistake-riddled bullshit. That might have been fair in 2023 or 2024. But it’s not accurate anymore.

Are AI companies gobbling up vast quantities of natural resources? Yes. Are their models built on the creative work of people without consent or compensation? Yes. Are these models hollowing out human relationships, connections, and work? Yes. Are they toxic for learning? Yes. But are LLMs just “autocomplete on steroids”? No. In the understandable drive to hold the AI industry to account for its many harms, we can’t keep moving the goalposts when it comes to evaluating what their products can actually do. Even if you are deeply opposed to generative AI, I think it’s important to have a clear-eyed understanding of where this technology currently stands.

In this post, I want to review some of the big developments of 2025 to show just how quickly this technology has advanced. Again and again, I’ve found that what many of my colleagues knew (or thought they knew) about generative AI twelve months or even six months ago is already outdated. One reason for this is that there’s an overwhelming amount of stuff out there to keep up with - library guides, Substacks, op-eds, podcasts, webinars, etc. Not only is it hard to sift through everything, but many of the resources on generative AI operate at such a high level that it’s difficult to know what it means for your specific job or discipline. This post tries to make things more concrete by looking back at some recent developments in generative AI through the lens of a historian: what changed in 2025 and what are the implications for the historical profession?

Multimodal Generation and History Slop

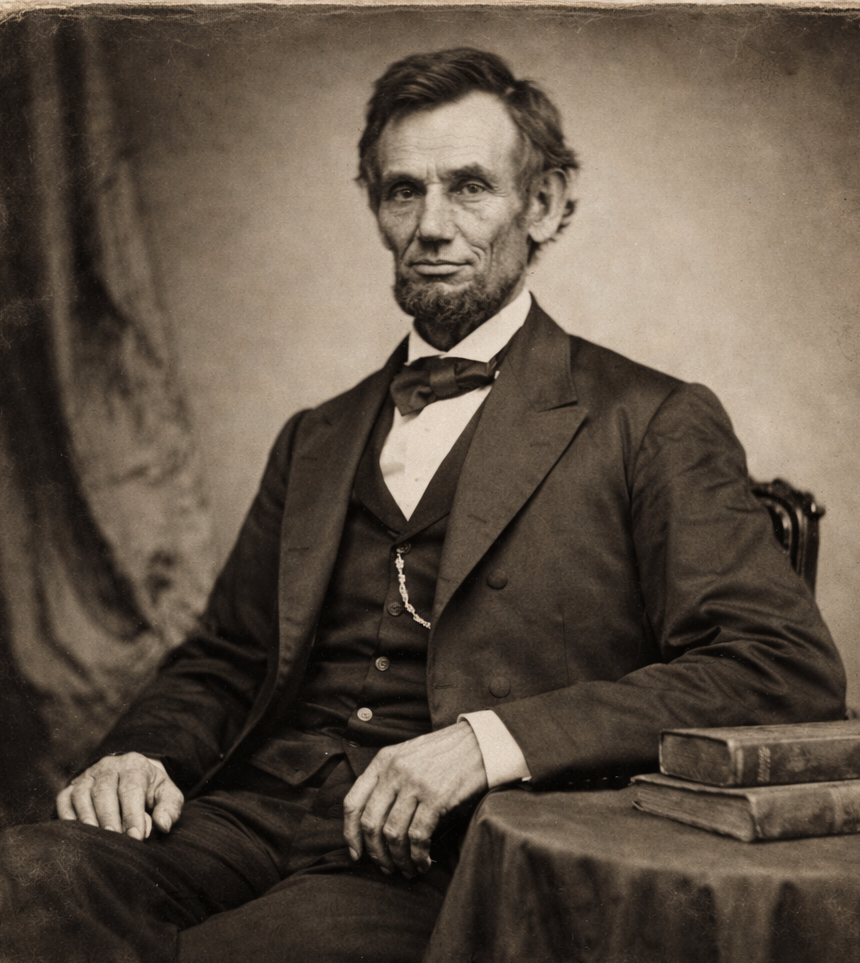

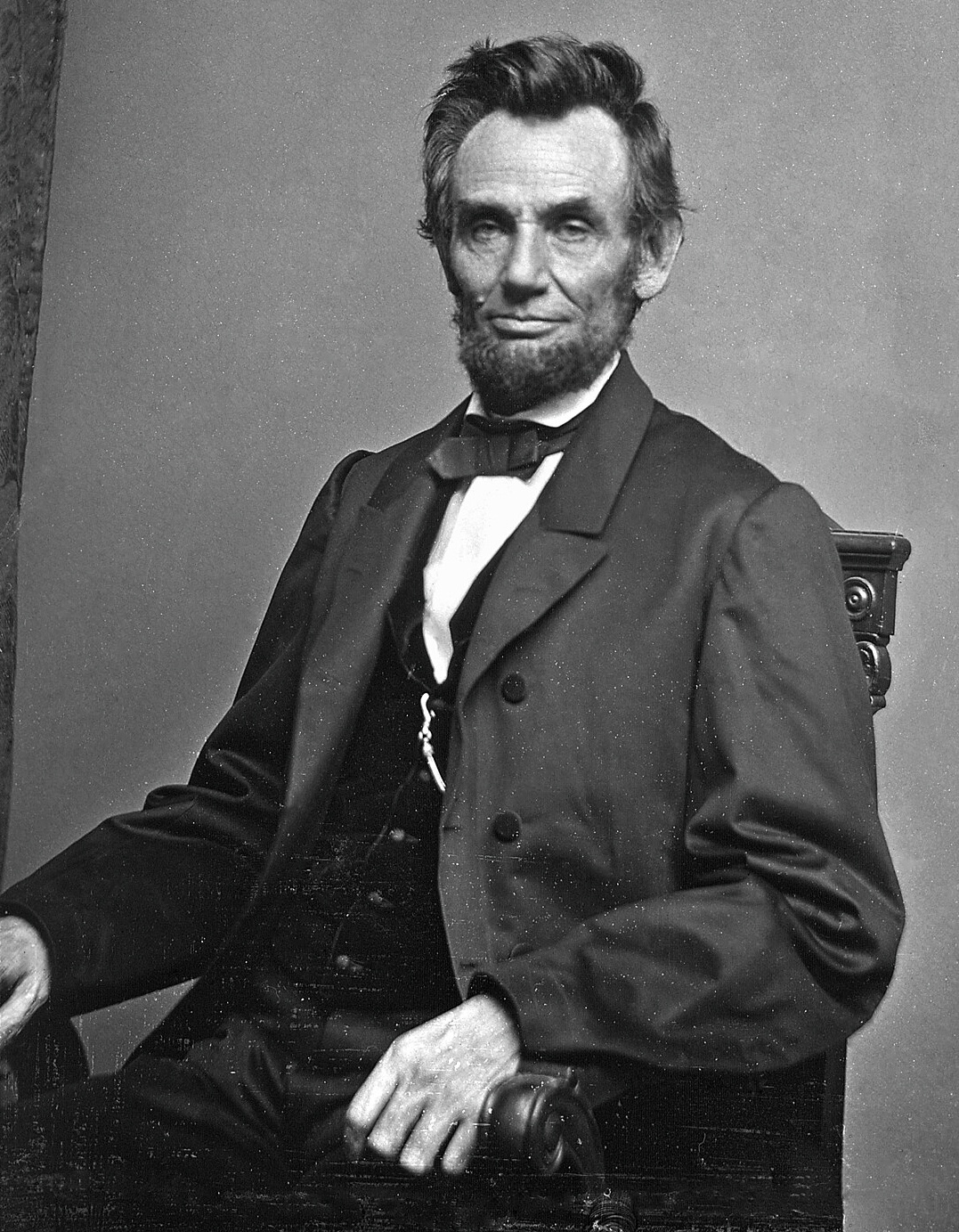

Let’s start with three images of Abraham Lincoln. Two of them are real photographs and one was made with ChatGPT. Give yourself 5-10 seconds and see if you can spot the fake. How confident are you? And how much money would you wager on your choice?

Click here to see which image was AI-generated.

Image 1: Image by ChatGPT (December 17, 2025)

Image 2: Photograph by Alexander Hesler (1860)

Image 3: Photograph by Mathew Brady (1864)

Whether or not you guessed correctly, this exercise illustrates a larger point: generative AI has gotten really good, really fast, at generating multimodal content, or stuff that isn’t just text (i.e. images, video, and audio). Over the past twelve months, we’ve gone from bizarre AI-generated photos with melted faces and six-fingered hands to images and videos that are increasingly difficult to distinguish from human-made ones.

Historical “deep fakes” have received a lot of deserved attention, but I’ve seen a lot less discussion of a far more pervasive issue: advances in multimodal generation have obliterated the barriers to producing synthetic historical videos at scale. The problem isn’t how realistic these videos look (most won’t fool you into thinking they’re “real”); it’s that multimodal generation has gotten so good (and so cheap) that it has already created a tidal wave of AI history slop.

Try searching YouTube for a historical event or historical figure and then filter your results to the last year of uploads; you will soon find yourself scrolling past AI-generated videos posted by users like ALLUSHISTORY or AmericanHistoryBufff:

Any historian interested in public engagement needs to pay attention to this development. Video (particularly short-form video) has come to dominate the media landscape. Social and video networks are now the most popular source of news for Americans of all ages, outpacing television, print, and online news sites for the first time. This is especially true for our current and future students: 3/4 of teenagers use YouTube every day, with TikTok not far behind. You can write all the op-eds and publish all the trade-press books you want; if you want to reach the public where it’s at in 2025, it’s video, video, video all the way down.

Content creators have been monetizing shitty history videos on YouTube for years. But until recently, making a successful video required at least some time and effort to put together (if no actual expertise). Recent jumps in multimodal generation has eliminated those barriers. Anyone, anywhere, can now make a polished-looking video on any historical topic at a very low cost and in a matter of minutes. No scriptwriting, no piecing together images, no audio recoring and editing; just type a few prompts and you have yourself a video.

The YouTube creator Historian Sleepy illustrates the changes unleashed by 2025’s advances in multimodal generation. Historian Sleepy has amassed 182,000 subscribers by posting history-themed videos for, you guessed it, people to fall asleep to. Each video is one long stream of AI-generated images and video clips about some general historical topic narrated by a soothing male voiceover, ranging from “How FRONTIER FAMILIES Survived The Coldest Nights and more” to “Who Were the Sumerians? The People Who Started Civilization” to “2 Hours of Life in the Gilded Age : 1880s America”:

The scale of output is staggering: each video runs 2 to 3 hours long and they’ve posted 286 of these multi-hour videos in just seven months - the equivalent of churning out a lengthy PBS documentary every single day (and sometimes multiple times a day). Each video has amassed tens of thousands of views. In 2025, academic historians are no longer competing for the public’s attention with the History Channel or bestselling “pop” history books; we’re competing with an ever-growing deluge of AI-generated history slop.

Deep Research

Multimodal generation was only part of the generative AI story in 2025. This year also saw the rise of reasoning and agentic models. To oversimplify, reasoning models break their responses down into smaller sequential steps (called “chain of thought”) and spend more time and computing power on generating an answer. This significantly improves responses and decreases hallucinations. Today, all the major frontier models offer this “reasoning” (sometimes called “thinking”) option. AI agents, meanwhile, use this “reasoning” architecture to come up with a plan for how to complete a task before taking a series of steps (often adjusting those steps as they go) in order to achieve that goal on their own.

For historians, the most direct application of these new reasoning and agentic capabilities came with the release of a “Deep Research” feature for all major frontier models. Selecting this feature sends the model off to browse the internet, sift through different sources of information, and synthesize all this material into a lengthy written report. If you rewind to the end of 2024, the ability of LLMs to locate reliable and credible sources was extremely poor, often returning bogus links to fabricated sources that didn’t exist. Twelve months later, that’s changed.

In September 2025, I tested out ChatGPT’s “Deep Research” feature by in my own particular area of expertise: the history of the American state in the American West. I selected the most advanced model available at the time (ChatGPT 5.1), selected the “Thinking” and “Deep Research” options, and instructed it to write “a historiographical essay on the current landscape of scholarship related to the history of the American state in the American West.” Over the next six minutes, the model conducted research and came back with a 7,000-word report.

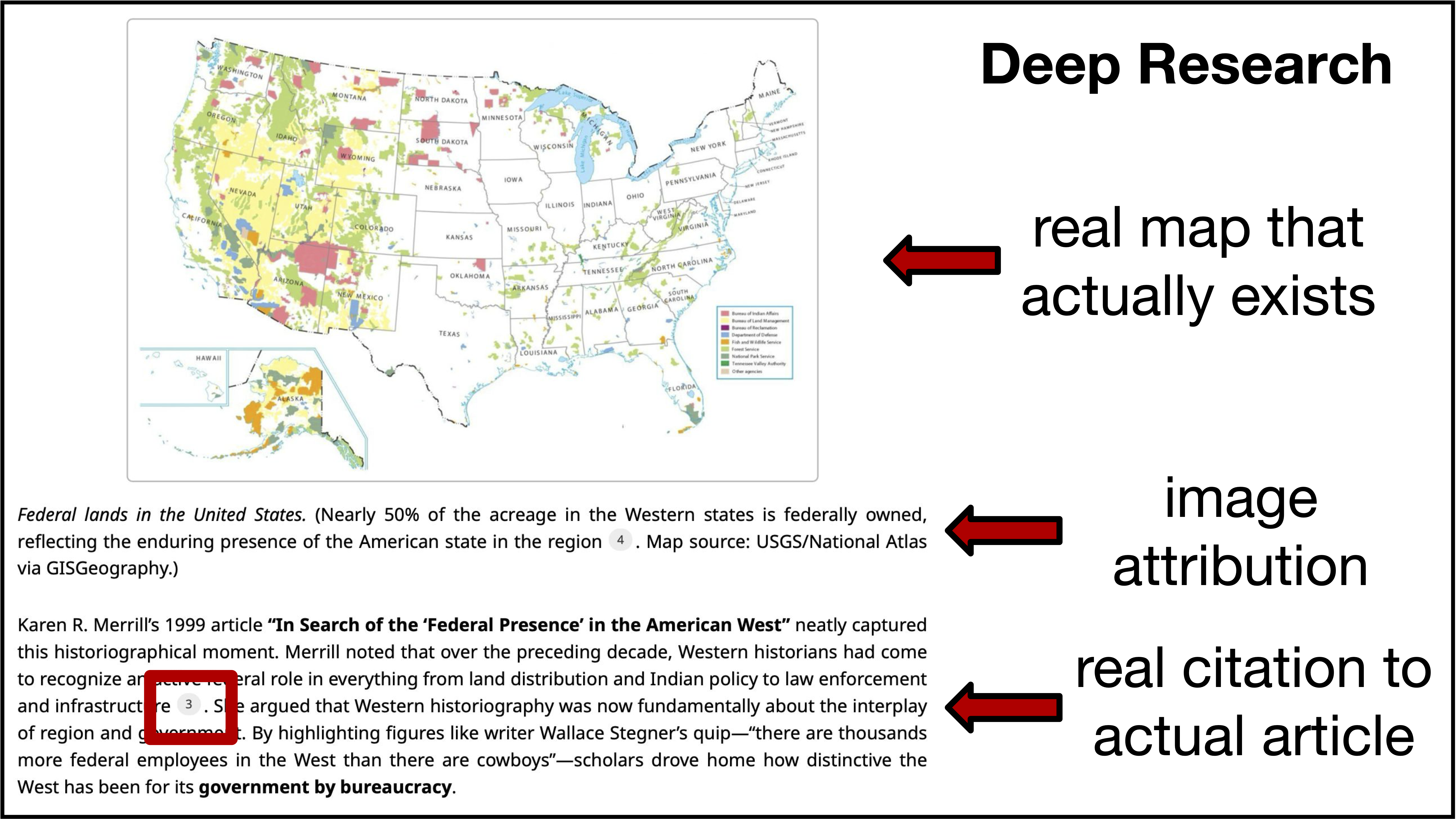

The report hit many of the major of the historiographical notes I would hope to see on this topic, from Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis” to American Political Development (APD) literature to the “New Western History” of the 1980s and 1990s to the more recent framework of “Greater Reconstruction.” It referenced work from a wide range of credible historians (Stephen Aron, Brian Balogh, William Cronon, Gary Gerstle, Sarah Barringer Gordon, Kelly Lytle Hernández, Beth Lew-Williams, Patricia Limerick, Benjamin Madley, Noam Maggor, Karen Merrill, William Novak, Margaret O’Mara, Elliott West, Richard White). There were no glaring mistakes, no fabricated citations to non-existent sources, no “10 Amazing Facts About the Wild West” websites - all things you would have found in a similar AI-generated essay in 2024. Hell, it even located and inserted (with full attribution) a map of federal land in the West, providing a compelling visual example of the state’s presence in the region:

Was it perfect? No. If I were writing this essay, I would have emphasized some different strands of scholarship or characterized certain trends differently. And there were other limitations, most notably a tendency to access and cite scholarship indirectly. To take one example, in summarizing William J. Novak’s article, “The Myth of the ‘Weak’ American State,” the model cited a Legal History Blog post…that itself was an excerpt of an AHA Today post…that itself summarized a roundtable in the American Historical Review…that was itself a discussion of Novak’s article in the American Historical Review. The reason for this game of scholarly telephone is that these models can’t, as of now, easily or directly access paywalled articles or full books. Even with this limitation, it did a remarkably accurate job of summarizing this scholarship. And, given the growing ability of AI agents to, say, log into databases using a user’s own credentials, I suspect the paywall issue won’t be a barrier for long.

Again, it’s important not to move the goalposts when evaluating this kind of output. If a graduate student had submitted this essay to me, I would have said they need be more concise and cite scholarship more directly, but otherwise would have been impressed with their command of the scholarly literature and how much material they managed to pull together into a coherent whole. I know this because I went back and compared the ChatGPT report to my own work in graduate school. It was, in certain respects, better than any historiographical essay I wrote as a PhD student (maybe I was an especially poor student). There is, of course, one final caveat: this particular “Deep Research” report was not conducting new, original research; it was a compilation of existing scholarship. This is precisely the kind of synthesis that LLMs should excel at. But if you want to dismiss this kind of report as derivative, unoriginal “fancy autocomplete,” then you need to similarly dismiss the historiographical essay as a bedrock genre of the historical profession.

Handwriting Transcription

Arguably the most notable development in generative AI for historians came in the realm of handwriting transcription. First, some background: the mass digitization of archival material has had a profound impact on historical research practices, and much of that impact came from making sources searchable and discoverable at scale. This required Optical Character Recognition (OCR), or using a computer to automatically transcribe historical documents. The problem is that a messy handwritten letter is a lot harder for a computer program to transcribe than neatly typed text. Although there have been major advances (most notably with the Transkribus platform), generally speaking computers make far more errors than human transcribers when it comes to handwritten historical sources.

The release of Google’s newest frontier model (Gemini 3.0) in November 2025 seems to have ushered in a new era for AI handwriting transcription. To illustrate this, I’m going to go into the weeds a bit and draw heavily from the work of historian Mark Humphries (I would encourage you to read his posts in full: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3).

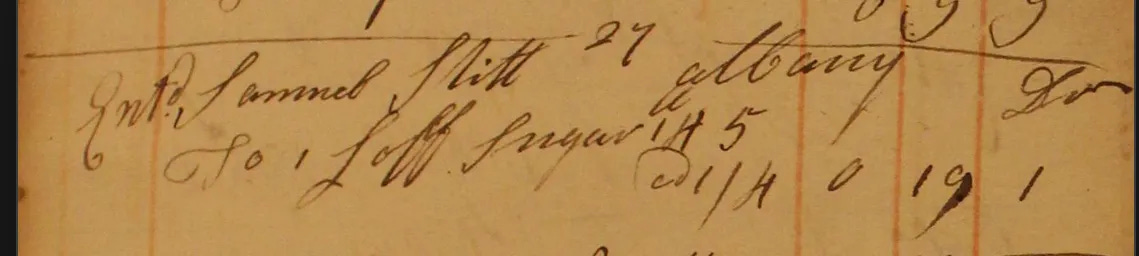

Mark tested out Gemini 3.0 with a handwritten accounting ledger kept by an Albany merchant in 1758. The document is a mishmash of numbers, dates, names, abbreviations, and columns - precisely the type of messy handwritten source that computers typically struggle to transcribe. Accurately deciphering this kind of document requires more than just visual accuracy (e.g. distinguishing a “4” from a “9”); you need to be able to analyze surrounding clues from the rest of the document and understand the historical context in which it was produced. In short, it requires reasoning, knowledge, and interpretation. Take this single entry from the ledger:

Gemini accurately transcribed the first line as Entd Samuel Stitt 27 albany Dr. This records one entry (Entd - entered) from March 27th, 1758 (27 - the month and year recorded at the top of ledger’s page) noting a purchase (Dr. - debit) made by an Albany-based merchant named Samuel Stitt.

The second line, however, is where the rubber hits the road. As a human reader, I would transcribe this as: 1 loff sugar 145 @1/4 0 19 1. However, unless you’re deeply versed in 18th-century British currencies, weights, and accounting practices (and are willing to do some math), you probably have no idea what this string of numbers actually means. I sure didn’t! But Gemini didn’t just transcribe these numbers. It went on to correctly interpret them as:

-

1loaf of sugar

- weighing

14lbs.5oz.

- at the rate of

1shilling,4pence per pound

- for a total cost of

0pounds,19shillings, and1penny

Gemini’s “reasoning trace,” where it explains how it reached this conclusion, is truly mind-blowing. Rather than interpreting 145 as, say, a running tally of how many loaves of sugar this merchant had bought over the past year or any number of other plausible but incorrect explanations, Gemini correctly identified it as a quantity of weight. It did so by conducting a series of calculations and conversions across multiple units of weight and currency to arrive at the result of 14 lbs. 5 oz. In Mark’s words, Gemini “was seemingly able to correctly recognize, convert, and manipulate hidden units of measurement in a difficult to decipher 18th century documents in ways that appear to require abstract, symbolic reasoning.” Again: we cannot keep pretending this is just “fancy autocomplete.”

Other historians have gotten similarly impressive results with Gemini 3.0. If it holds, this development has huge implications for historical research. Many digital collections have skewed towards printed, typewritten sources over handwritten ones in large part because of the challenges and costs of transcribing handwritten sources. But if LLMs like Gemini can now consistently rival the abilities of human typists, and at much lower costs across much larger scales, they will open up a new era for digital archives and, by extension, archival research.

Taking Stock

All three of the areas I’ve described here - multimodal generation, Deep Research, and handwriting transcription - have changed dramatically in the past twelve months. YouTube is now flooded with thousands of hours AI history slop that didn’t exist in 2024. With a single prompt, students can generate lengthy historiographical essays that would have been riddled with hallucinations in 2024. Archivists and researchers can use LLMs to transcribe handwritten sources with a degree of accuracy and sophistication that was impossible in 2024. Twelve months ago, all of this would have seemed far-fetched; twelve months from now, this post might be outdated. This is why I think it’s so important for historians to continue to keep pace with these developments.

Here is where I should offer some brilliant pronouncements about how to grapple with these changes. But I’ll be completely honest: I don’t have them. I don’t have a roadmap for responding to all of this. What I do know is that dismissing generative AI as just “autocomplete on steroids” is no longer tenable. We can’t reckon with this technology’s harms and benefits while clinging to outdated characterizations of its capacities. Understanding what generative AI can actually do - and how quickly those capacities are changing - is a necessary first step before we can sort through what it all means for our profession.