Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

At 3AM on April 25, 2009, I will join several hundred other participants and attempt to walk 100 kilometers (62 miles) in one day along the C&O Canal towpath, from Georgetown, D.C. to Harper’s Ferry, West Virgina. To mentally prepare for this foolhardy attempt, I thought I’d briefly walk through the canal’s history.

The canal’s history as a functional transport artery is something of a prolonged tragedy. The story begins, like most tragedies, with a seemingly idyllic birthright: the canal was first championed by none other than George Washington, who also, it should be remembered, championed such things as non-partisanship, presidential term limits, and the United States of America. Apparently in his younger years, George was something of a canal enthusiast, going so far as to introduce a 1774 bill in the Virginia legislature to construct canals around obstacles in the Potomac River. Even in his presidency, George continued to lobby hard for a canal extending from the nation’s capitol and viewed it as a critical piece of his broader vision for consolidating national cohesion and opening up commerce and communications with the west:

'"Extend the inland navigation of the eastern waters; communicate them as near as possible with those which run westward; open these to the Ohio; open also such as extend from the Ohio towards Lake Erie; and we shall not only draw the produce of the western settlers, but the peltry and fur trade of the lakes also, to our ports: thus adding an immense increase to our exports, and binding those people to us by a chain which never can be broken.'"

From Memoirs of De Witt Clinton, transcribed by Bill Carr

Armed with the ringing endorsement of one America’s most hagiograph-ied figures, the future C&O Canal looked destined to join the ranks of Route 66, the Union Pacific Railroad, and, yes, the Erie Canal, in the annals of transportation lore. By the 1820’s, a perfect storm brewed. The case for the C&O Canal was buoyed by the lucrative success of its northern cousin. Proposed in 1808 and beginning construction in 1817, the Erie Canal took little time to start turning a profit as toll revenues poured in from already-completed sections. The Canal had a profound effect on the region and country, establishing New York City as the nation’s premiere commercial center and acting as a poster child for the infrastructure boom of the 1820’s.

Digging a little deeper (pun intended) however, revealed fundamental weaknesses underlying the C&O Canal’s prospects to follow in the Erie’s footsteps. Construction began in 1828, as John Quincy Adams dug the first spadeful of earth. Fittingly for the canal, his attempt at ceremonial ground-breaking met with an unforeseen obstacle:

“It happened that at first stroke of the spade it met immediately under the surface with a large stump of tree after repeating the stroke three or four times without making any impression threw off my coat and resuming the spade, raised a shovel full of the earth at which a general shout broke forth from the surrounding multitude and I completed my address which occupied about fifteen minutes.”

John Quincy Adams

JQA Diary, number 36, 1 January 1825-30 September 1830, page 21

Beginning with this nearly-bungled case of presidential midwifery, it was all downhill from there. Five years after its construction, the canal had only progressed 60 miles, and was not yet fully operational. In hindsight, beginning construction on a canal in 1828 was poor timing. The meteoric pace of internal improvements during this period may have spurred the impetus for building the canal, but also created an infrastructure bubble that left it open to significant competition and unrealistic expectations.

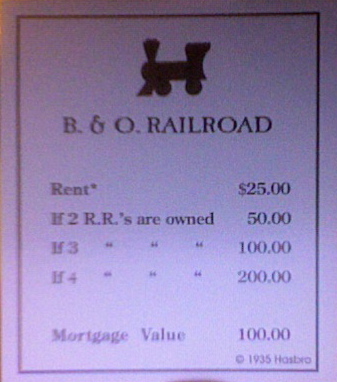

In particular, the canal found itself embroiled with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad over land-use rights along the Potomac. Although the two sides settled their dispute, the legal wrangling was symptomatic of the canal's slow-going construction and never-ending obstacles. The B&O Railroad, which began construction on the same day as the C&O Canal, progressed far smoother, and provided a significant advantage to its clients in speed of transport. The C&O finally reached Cumberland, Maryland (linking it to the National Road) and promptly ceased construction. The B&O Railroad completed the all-important link to the Ohio River in West Virginia in 1852, usurping the canal's purpose and rendering the slow-moving waterway somewhat moot. Which is why the B&O Railroad, instead of the C&O Canal, garnered eternal fame as a one of Monopoly's prized properties:

The canal remained nominally operational until 1924, when a catastrophic flood wreaked havoc on the transport system, and in 1938 the canal was sold to the federal government. By the 1950's, in the wake of another national transportation boom, Congress entertained the idea of paving over the canal to build a scenic road for automobiles. Fortunately for canal lovers, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas assumed the mantle of George Washington to become the canal's next great champion in Washington.

In an impassioned letter to the Washington Post in 1954, the nature-loving Douglas channeled his inner John Muir when he wrote, "It is a refuge, a place of retreat, a long stretch of quiet and peace at the Capitol's back door - a wilderness area where we can commune with God and with nature, a place not yet marred by the roar of wheels and the sound of horns." He then threw down the gauntlet as only a tree-hugging Supreme Court Justice of the 1950's could do: by challenging proponents of paving the canal to walk its entire 184.5 miles with Douglas as their guide.

Perhaps to Douglas's surprise, his challenge was not only accepted, but snowballed into a media spectacle. Fifty-seven people joined him on March 20, 1954 to begin hiking the trail. Although only nine of them finished the eight-day hike (many were discouraged by a snowstorm on the second day of the trip), Douglas's expedition garnered national attention, as flocks of reporters interviewed the justice and his hikers, and onlookers showered the walkers with cheers and food. By the conclusion of the hiking circus, public support had swung towards preserving the C&O Canal.

The publicity stunt ended up saving the canal, and in 1971 the federal government designated the C&O Canal a National Historic Park. Today the canal remains a popular get-away for D.C.-area residents, who can walk, bike, jog, kayak, or in Douglas’s words (if they are in a particularly spiritual mood), “commune with God and with nature.” When plodding along the canal on Saturday, I will try to remember a poem stanza composed by Douglas’s hikers while on trail:

The knees are slowly playing out The arches start to drop; If we had John Brown's body here, We'd like to make a swap.