A Dissertation’s Infancy: The Geography of the Post

A history PhD can be thought of as a collection of overlapping areas: coursework, teaching, qualifying exams, and the dissertation itself. The first three are fairly structured. You have syllabi, reading lists, papers, classes, deadlines. The fourth? Not so much. Once you’re advanced to candidacy there’s a sense of finally being cut loose. Go forth, conquer the archive, and return triumphantly to pen a groundbreaking dissertation. It’s exhilarating, empowering, and also terrifying as hell. I’ve been swimming through the initial research stage of the dissertation for the past several months and thought it would be a good time to articulate what, exactly, I’m trying to find. Note: if you are less interested in American history and more interested in maps and visualizations, I would skip to the end.

The Elevator Speech

I'm studying communications networks in the late nineteenth-century American West by mapping the geography of the U.S. postal system.*

The Elevator-Stuck-Between-Floors Speech

From the end of the Civil War until the end of the nineteenth century the US. Post steadily expanded into a vast communications network that spanned the continent. By the turn of the century the department was one of the largest organizational units in the world. More than 200,000 postmasters, clerks, and carriers were involved in shuttling billions of pounds of material between 75,000 offices at the cost of more than $100 million dollars a year. As a spatial network the post followed a particular geography. And nowhere was this more apparent than in the West, where the region’s miners, ranchers, settlers, and farmers led their lives on the network’s periphery. My dissertation aims to uncover the geography of the post on its western periphery: where it spread, how it operated, and its role in shaping the space and place of the region.

My project rests on the interplay between center and periphery. The postal network hinged on the relationship between its bureaucratic center in Washington, DC and the thousands of communities that constituted the nodes of that network. In the case of the West, this relationship was a contentious one. Departmental bureaucrats found themselves buffeted with demands to reign in ballooning deficits. Yet they were also required by law to provide service to every corner of the country, no matter how expensive. And few regions were costlier than the West, where a sparsely settled population scattered across a huge area was constantly rearranged by the boom-and-bust cycles of the late nineteenth century. From the top-down perspective of the network’s center, providing service in the West was a major headache. From the bottom-up perspective of westerners the post was one of the bedrocks of society. For most, it was the only affordable and accessible form of long-distance communication. In a region marked by transience and instability, local post offices were the main conduits for contact with the wider world. Western communities loudly petitioned their Congressmen and the department for more offices, better post roads, and speedier service. In doing so, they redefined the shape and contours of both the network and the wider geography of the region.

The post offers an important entry point into some of the major forces shaping American society in the late nineteenth century. First, it helped define the role of the federal government. On a day-to-day basis, for many Americans the post was the federal government. Articulating the geographic size and scale of the postal system will offer a corrective to persistent caricatures of the nineteenth-century federal government as weak and decentralized. More specifically, a generation of “New Western” historians have articulated the omnipresent role of the state in the West. Analyzing the relationship between center and periphery through the post’s geography provides a means of mapping the reach of federal power in the region. With the postal system as a proxy for state presence, I can begin to answer questions such as: where and how quickly did the state penetrate the West? How closely did it follow on the heels of settler migration, railroad development, or mining industries? Finally, the post was deeply enmeshed in a system of political patronage, with postmasterships disbursed as spoils of office. What was the relationship between a communications network and the geography of regional and national politics?

Second, the post rested on an often contentious marriage between the public and private spheres. Western agrarian groups upheld the post as a model public monopoly. Nevertheless, private hands guided the system’s day-to-day operations on its periphery. Payments to mail-carrying railroad companies became the department’s single largest expenditure, and it doled out millions of dollars each year to private contractors to carry the mail in rural areas. This private/public marriage came with costs - in the early 1880s, for instance, the department was rocked by corruption scandals when it discovered that rural private contractors had paid kickbacks to department officials in exchange for lavish carrying contracts. How did this uneasy alliance of public and private alter the geography of the network? And how did the department’s need to extend service in the rural West reframe wider debates over monopoly, competition, and the nation’s political economy?

Getting Off The History Elevator

That’s the idea, at least. Rather than delve into even greater detail on historiography or sources, I’ll skip to a topic probably more relevant for readers who aren’t U.S. historians: methodology. Digital tools will be the primary way in which I explore the themes outlined above. Most obviously, I’m going to map the postal network. This entails creating a spatial database of post offices, routes, and timetables. Unsurprisingly, that process will be incredibly labor intensive: scanning and georeferencing postal route maps, or transcribing handwritten microfilmed records into a database of thousands of geocoded offices. But once I’ve constructed the database, there are any number of ways to interrogate it.

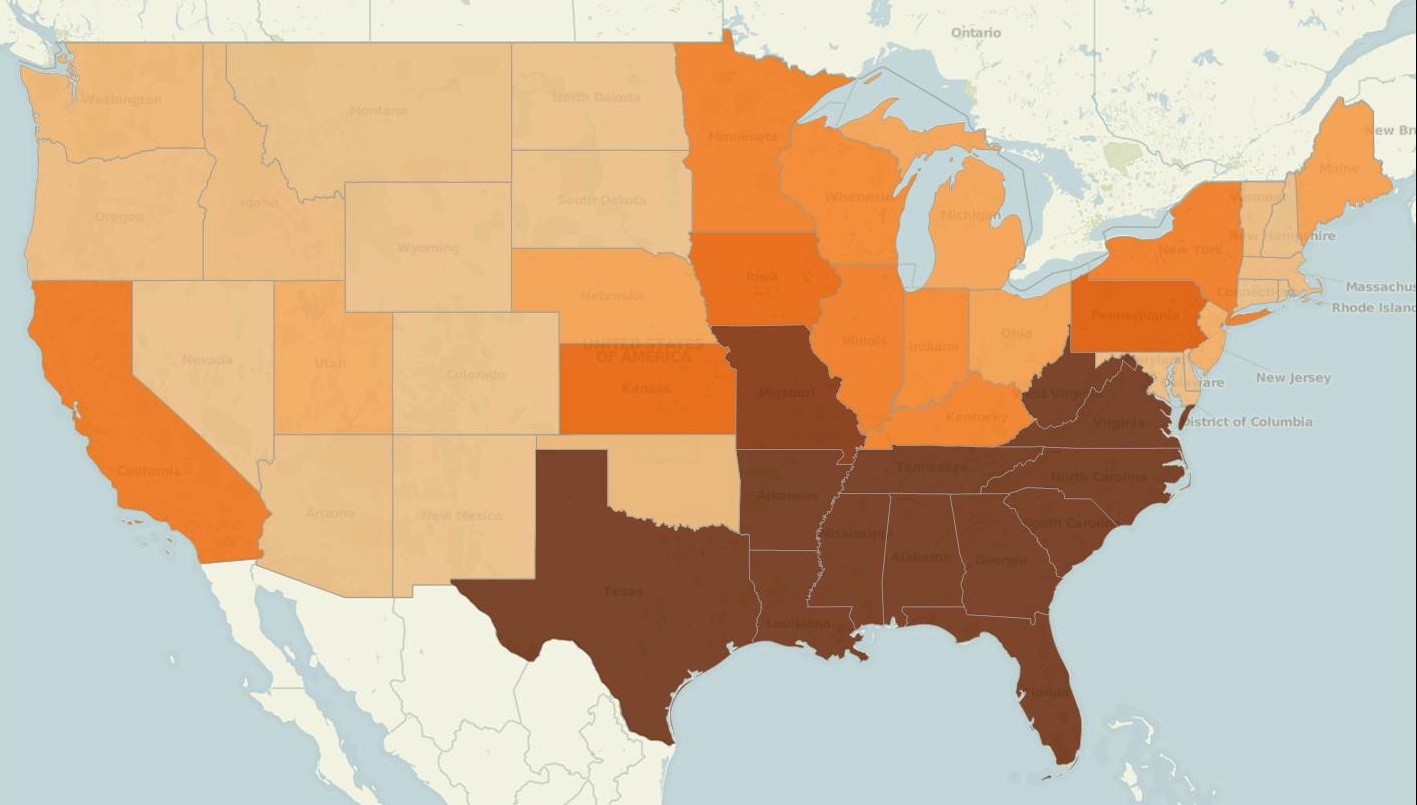

To demonstrate, I’ll start with lower-hanging fruit. The Postmaster General issues an annual report providing (among other information) data on how many offices were established and discontinued in each state. These numbers are fairly straightforward to put into a table and throw onto a map. Doing so provides a top-down view of the system from the perspective of a bureaucrat in Washington, D.C. For instance, by looking at the number of post offices discontinued each year it’s possible to see the wrenching reverberations of the Civil War as the postal system struggled to reintegrate southern states into its network in 1867:

Post Offices Discontinued By State, 1867 (Source: Annual Report of the Postmaster General, 1867)

Post Offices Discontinued By State, 1867 (Source: Annual Report of the Postmaster General, 1867)

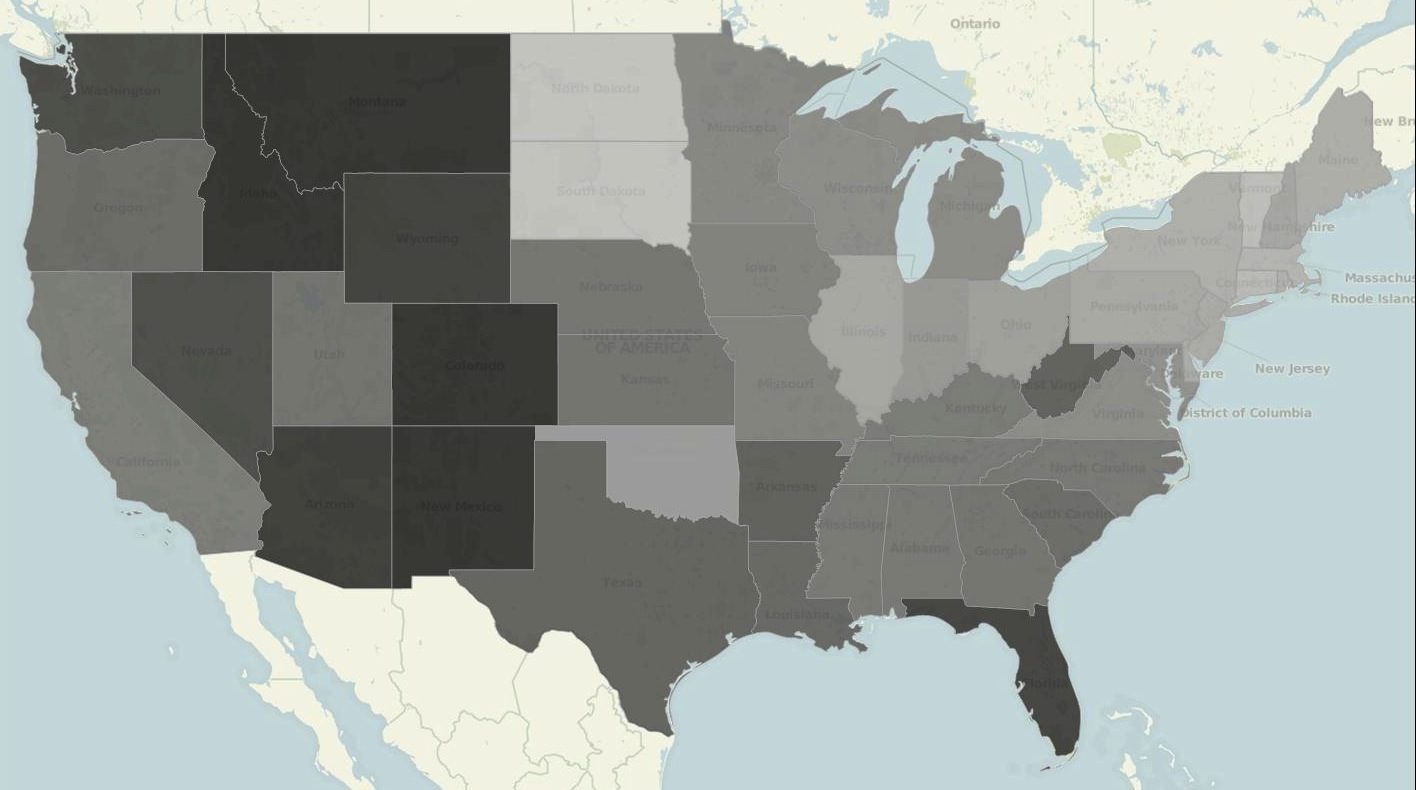

The West, meanwhile, was arguably the system’s most unstable region. As measured by the percentage of its total offices that were either established or discontinued each year, states such as New Mexico, Colorado, and Montana were continually building and dismantling new nodes in the network.

Post Offices Established or Discontinued as a Percentage of Total Post Offices in State, 1882 (Source: Annual Report of the Postmaster General, 1882)

Post Offices Established or Discontinued as a Percentage of Total Post Offices in State, 1882 (Source: Annual Report of the Postmaster General, 1882)

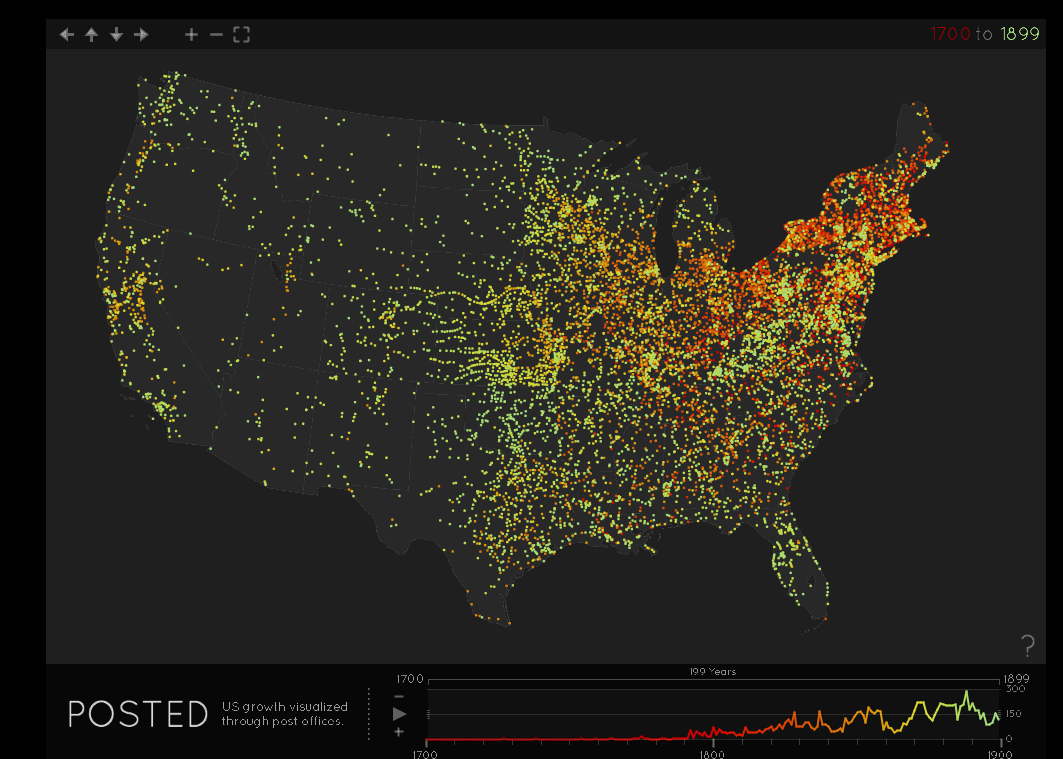

Of course, the broad brush strokes of national, year-by-year data only provide a generalized snapshot of the system. I plan on drilling down to far more detail by charting where and when specific post offices were established and discontinued. This will provide a much more fine-grained (both spatially and temporally) view of how the system evolved. Geographer Derek Watkins has employed exactly this approach:

Screenshot from Derek Watkins, "Posted: U.S. Growth Visualized Through Post Offices" (25 September 2011)

Screenshot from Derek Watkins, "Posted: U.S. Growth Visualized Through Post Offices" (25 September 2011)

Derek’s map demonstrates the power of data visualization: it is compelling, interactive, and conveys an enormous amount of information far more effectively than text alone. Unfortunately, it also relies on an incomplete dataset. Derek scraped the USPS Postmaster Finder, which the USPS built as a tool for genealogists to look up postmaster ancestors. The USPS historian adds to it on an ad-hoc basis depending on specific requests by genealogists. In a conversation with me, she estimated that it encompasses only 10-15% of post offices, and there is no record of what has been completed and what remains to be done. Derek has, however, created a robust data visualization infrastructure. In a wonderful demonstration of generosity, he has sent me the code behind the visualization. Rather than spending hours duplicating Derek’s design work, I’ll be able to plug my own, more complete, post office data into a beautiful existing interface.

Derek’s generosity brings me back to my ongoing personal commitment to scholarly sharing. I plan on making the dissertation process as open as possible from start to finish. Specifically, the data and information I collect has broad potential for applications beyond my own project. As the backbone of the nation’s communications infrastructure, the postal system provides rich geographic context for any number of other historical inquiries. Cameron Ormsby, a researcher in Stanford’s Spatial History Lab, has already used post office data I collected as a proxy for measuring community development in order to analyze the impact of land speculation and railroad construction in Fresno and Tulare counties.

To kick things off, I’ve posted the state-level data I referenced above on my website as a series of CSV files. I also used Tableau Public to generate a quick-and-dirty way for people to interact with and explore the data in map form. This is an initial step in sharing data and I hope to refine the process as I go. Similarly, I plan on occasionally blogging about the project as it develops. Rather than narrowly focusing on the history of the U.S. Post, my goal (at least for now) is to use my topic as a launchpad to write about broader themes: research and writing advice, discussions of digital methodology, or data and visualization releases.